A few months back, my son downloaded the latest edition of The Show to our Nintendo Switch, and we immediately transferred our ongoing grudge match from NBA2K to the new game. A couple weeks after that, I used the White Sox to trounce him 23-4 behind a dozen strikeouts from Dylan Cease.

I texted him the following day while he was in school, informing him that his stepmom had called the cops on me for child abuse. He later admitted that his heart skipped a beat and he momentarily panicked upon hearing this insane update coming out of left field.

After letting it sink in for a moment, I added that she had reported me for savagely beating him 23-4 in The Show the previous evening. He took a deep breath on the other end of the line, cursed me, and I had a good laugh.

What does this episode say about me? You know, beyond making you question whether I’m actually fit to raise children? To me, it’s proof that I enjoy baseball video games. (And possibly that my sense of humor is a tad twisted.)

The part about baseball video games is definitely true though. The Show is a fantastic game too, easily the most realistic simulation of baseball that I’ve ever played. I don’t go in for dynasty mode like my son. I’m not worried about developing an avatar version of me from the minors. But the gameplay itself is second to none.

It’s extremely cool to control the real players in digital versions of ballparks so detailed that they really do seem to come alive. Although I’ll never understand why the crowd is always so sparse in the stands. MLB can’t even pack the seats in their own video game? That’s depressing.

My favorite part of the game is pitching. I love the strategy of calling different pitches and locations. There’s something deeply satisfying about working the corners early in the count to set up a swing and miss on a backdoor changeup for the punch-out. It’s probably the closet I’ll ever get to standing on a big league mound. That’s the power of a good sports-based video game.

My major league dreams died relatively early. My own little league pitching career was pedestrian, I lacked anything remotely resembling the speed on the basepaths of two of my heroes, Willie Wilson and Rickey Henderson, and an extended slump at the plate during my post-eighth grade season even made me question one of the more dependable aspects of my game.

Couple all that with my high school’s lack of a baseball program, and it became abundantly clear at a young age that my playing days were numbered. Thankfully, the baseball gods didn’t want to lose me forever, and they sent a lifeline in March 1994. That was when Ken Griffey Jr. Presents Major League Baseball was released for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System.

Two video games stand head and shoulders above every other game I’ve played. (And before the Mario and Zelda fans get offended, keep in mind that we’re talking specifically about sports games right now.) The first was Tecmo Super Bowl for the NES, but it’s a football game, and since it has no connection to baseball, other than the inclusion of Bo Jackson, I’m not going to talk about it here.

The other game, of course, was Ken Griffey Jr. Presents Major League Baseball, which will simply be referred to as Griffey moving forward. It’s incredibly crude compared to the latest edition of The Show, but no video game has provided me with more hours of entertainment over the course of my life.

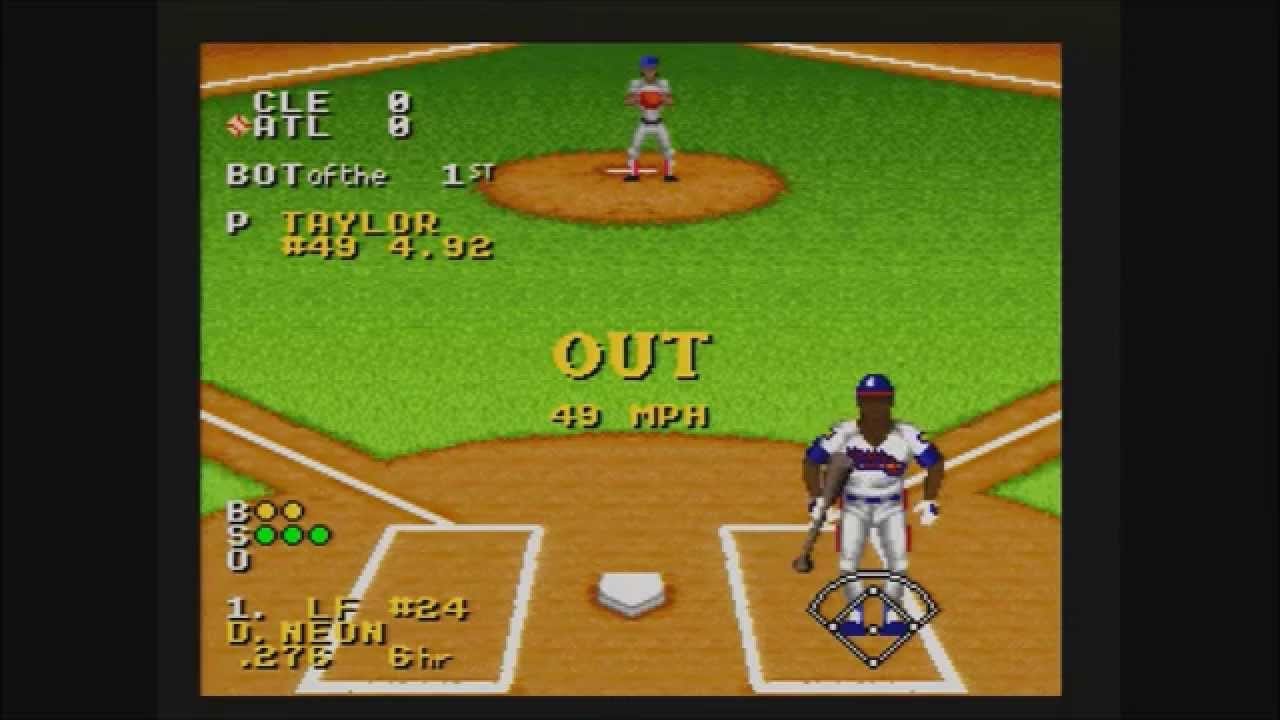

The simplicity of its gameplay is the chief thing that Griffey has going for it. Hitting is basic and primarily a matter of timing. Pitching is uncomplicated and straightforward. There’s no selection of specific pitches. You simply hit the B button and hold up or down to control speed. The left and right buttons control placement. This doesn’t provide much in the way of realism, but especially when you’re playing against another person, a 50 mph changeup can be remarkably effective.

Each direction on the control pad corresponds to a base. Hold down the correct base and press B to throw the ball around the horn on defense. Do the same and press A on offense to run the bases. A mini-diamond in the corner of the screen helps you follow the action on the bases and features a blue X to track the ball on defense.

This was something that many later games failed to grasp completely. They added more and more bells and whistles in attempts at greater authenticity, but generally succeeded in only making Griffey’s successors more complicated and aggravating. This is true even of Griffey’s own direct sequels (one for SNES, two for N64), none of which capture the original’s joyful simplicity.

The online reviews for the game are surprisingly mixed, based on my own positive experiences. But the more I think about it, the more appropriate this seems. The game truly is a mixed bag. So many parts of it are fantastic, but it has its fair share of flaws and shortcomings. Fortunately, most of these only make the game more endearing.

Like The Show, Griffey attempts to recreate MLB stadiums. Only, it does kind of a half-ass job of it. I’m not criticizing the graphics themselves. In fact, these are quite good for the time, though they obviously fall well short in their level of detail compared to The Show. That said, there was something very cool about hitting one to the ivy at Wrigley back in the day, or sending a ball into the fountains at Kauffman. They even had the Crown Vision scoreboard in center field.

The designers only attempted to faithfully recreate some of the stadiums, however. I don’t know if this was due to space limitations in the SNES cartridge’s memory, time constraints, laziness or what. But while Fenway has the Green Monster, Yankee Stadium features its short right field porch, and Tiger Stadium’s distinctive upper deck is instantly recognizable, many of the other venues share a generic layout.

Perhaps the most frustrating aspect of the game was its lack of real players. Except for the title character, who was an excellent choice by the way— Griffey was one of the most talented players in the league, and arguably its most recognizable and likable face— no other real players are featured in the game. Well, sort of. This is where it gets kind of confusing.

The game’s makers could not come to an agreement with the MLBPA, so while it includes the real teams, the players are all made up. In fact, this is one of the most memorable parts of the game, since the names for each team’s players are inspired by different themes.

Some of these are instantly recognizable. For example, the Kansas City Royals are all named after former U.S Presidents. C Mike MacFarlane is A. Lincoln. 1B Wally Joyner is G. Cleveland. George Brett is D. Ike. That’s Eisenhower, for those of you who flunked U.S. history.

The Boston Red Sox are named after characters from Cheers. Oakland and Cincinnati both use the names of famous writers. The Rockies share their monikers with horror movie icons. The Brewers are made up of superhero secret identities.

Other teams aren’t as obvious. The White Sox are all named after former St. John’s basketball players. Toronto’s players share their names with players from the Wigan Warriors rugby squad. The Mariners, except for Griffey, are employees of Nintendo of America. The Giants’ lineup is like an informal credits sequence, taking its names from people who worked on the game. And the Marlins are named after kids in the director’s elementary school class.

But if you noticed when I was mentioning the Royals, each made-up name corresponded to a real player. This was the loophole. The lineups are taken from the 1993 season, and the players are easily identifiable, even with the fake names, based on their positions, batting order, and 1993 statistics. Their ratings in four different skill categories— batting, power, speed, and defense— also sync up with their real profile.

They don’t actually look like the real players— again, with the exception of Griffey. Instead, the game uses a dozen or so general body templates and attempts to match them with players according to their skill sets. Speedsters like Kenny Lofton and Brett Butler tend to be short and skinny, while sluggers like Mark McGwire and Albert Belle are bulky behemoths with bulging upper bodies. With the exception of one or two glitches, they assigned the correct race and ethnicity to individual players.

A few of the body types border on the absurd. The first one that always comes to mind is Wade Boggs, who has a stout and muscular upper body paired with comically skinny chicken legs. I don’t know if that had anything to with Boggs’ nickname being “the Chicken Man,” but considering he’s not the only one with this ridiculous profile, I assume it was just a coincidence.

The game also allowed you to edit the players’ names. Of course, this required a level of patience that most people probably didn’t possess, but if you desired to make the game more realistic, you had the option to go in and type the real names for every player on all twenty-eight rosters. Or even better, you could update the rosters as they turned over in the years that followed.

You better believe I did that. In fact, I did it several times, because like many SNES games, Griffey had the habit of occasionally resetting saved data for no good reason. Sometimes it could be a small thing, like a glitch that often reset your top slugger’s home run total after the All-Star break. Other times, it would wipe the whole system clean.

This could be incredibly frustrating, especially if it happened late in a 162-game season, because there was nothing you could do about it except start over from scratch. And because I was committed to making the experience as authentic as possible, I would begrudgingly restart the whole laborious process of reentering all the correct names.

This commitment to authenticity was also why I insisted on playing full 162 game seasons, despite the threat of resets, even though it gave you the option of playing 26 or 78 game seasons instead. Playing fewer games would throw off the stats, so I never considered it a real option.

I can remember finishing two complete seasons for sure back in the 90’s. Because it was introduced between the 1993 and 1994 seasons, players had the option of using either the old two division format or the new realigned three division format with a wild card team in the playoffs. Again, out of consideration for the new reality, I always chose the latter.

I won two world championships, one with the Royals and the other courtesy of the Yankees. I think I had the season stats for both written down in a notebook once upon a time, but I’ve long since lost track of it. I can still recall a few vague details though.

I remember that Kevin Appier and David Cone formed a dominant 1-2 punch at the top of my rotation for KC. I also know that I went 152-10 with the Yankees, which was really good. Beating the computer wasn’t especially difficult, but unlike other sports games, it was impossible to go undefeated in Griffey. There were too many games, and sometimes, no matter what you did, the computer was going to find a way to beat you.

That was okay, because the overall importance of Griffey to my personal baseball experience cannot be exaggerated. You might have noticed that the game was released near the end of the period covered by this newsletter, at a time in my life when baseball was rapidly decreasing in importance. I was getting more interested in girls, books, music, and a host of other things, both healthy and not so beneficial.

Yet, as I spent less time checking box scores and obsessing over the standings in the morning paper, and more time thinking about what I was going to do with my friends on a Friday night, Griffey served as a lifeline. Well, no, lifeline is probably far too strong a word, now that I think about it. But it kept me connected to the game at a time when the threat of losing touch altogether was very real, and paved the way for baseball’s eventual return to prominence in my life.

No matter what was going on in my turbulent teenage life, I could come home and retreat to my room and blow off steam by switching on the SNES. As time went on, I was less worried about entering in the real names, and I eventually gave up on trying to play complete seasons. (Fortunately, Griffey had a World Series option that allowed you to pick your team and play a best of seven series against another player or the computer.) All that mattered was that it was still fun to play.

I moved away to college and the SNES didn’t make the trip. By then, my interest in baseball was on life support, but it had been reinforced enough to keep it going throughout the remaining lean years without the assistance of a now severely outdated video game. If I thought of Griffey at all during that period, it was only in terms of nostalgia. I doubted I would ever play it again.

Nearly two decades later, my cousin Scott dug his SNES out of his mom’s basement and went online to buy a copy of Griffey. He invited me over to play a game, and I thought, what the hell? Could be fun. Little did I realize we were relaunching a new obsession.

The two of us have played on a regular basis for the last five years. It started out with random games here and there, often in between watching real baseball games or other sporting events on TV. It seemed like as good a reason to hang out as any. Now it’s often the driving force behind our social interactions.

We typically play only World Series against each other now, switching back and forth between first and second player because the game has a weird glitch that affects the availability of the second player’s pitching staff in World Series mode. It’s annoying and a definite disadvantage, but we’ve both played enough series now that we’re pretty adept at working around it.

Two years ago, I found a used Darren Daulton Starting Lineup figurine on sale for a dollar at a collectible shop. I bought it and we made it our Griffey World Series trophy. I also started keeping official records in a notebook, recording the results of each series, naming an MVP, and noting any other significant accomplishments, both good and bad, for each matchup.

For example, I can tell that I once hit five home runs with Jay Buhner in a losing effort. Kevin Reimer of the Brewers hit 4 home runs for Scott in a 4-2 series win over me while playing with the Twins. Perhaps my most heartbreaking moment came when I pitched twelve innings of no-hit ball with Sid Fernandez, only to lose the no-no in the 13th and the game in 14 innings because I was incapable of scratching out a single run myself.

At the beginning of last year, we retired the Daulton figure and replaced him with Daryl Strawberry. I wish I could say that he’s spent more time at my house than Scott’s, but Griffey has been a struggle for me since Strawberry’s introduction at the beginning of 2022. My overall record during that span is 2-13, with only the Astros and Rangers claiming victories for me. At the least the state of Texas has treated me right.

On the one hand, it’s incredibly frustrating. Griffey doesn’t require a lot of pure skill. I have a tendency to make the occasional costly error— DERP!— but it mostly boils down to random chance and the computer’s will. Plus, I’ve been playing for nearly thirty years. I’ve never struggled this bad, and I didn’t suddenly forget how to play. Here’s hoping the introduction of a new Jack McDowell trophy in 2023 will change my fortunes.

Not that it really matters. The thought of quitting or switching to another game has never crossed my mind. I enjoy playing The Show with my son, and it’s his preferred game because he didn’t grow up with Griffey, but Griffey will always be number one in my rankings. It’s still the most fun video game I’ve ever played.

I can’t imagine you need further evidence of that. I’ve given you insight into previously unrevealed levels of my nerdom to praise it. Sure, I’ve grown up a little over the years, but clearly not that much. I no longer feel the need to enter in the correct lineups player by player, but type 19 into Google on mine or Scott’s phone and it will suggest a long list of 1993 baseball team rosters. We both like to have that reference point.

I used to ask my mom if I could go play video games at a friend’s house. Now I’m a forty-three-year old man, and I regularly ask my wife if she’s okay with me going over to Scott’s to play Griffey. She’ll probably cringe at that comparison, but it’s accurate in this particular respect.

And I, for one, can’t imagine better proof that baseball, even in its most indirect form, keeps us young at heart forever.

Thanks for reading Powder Blue Nostalgia. What are your Griffey memories? Is there another baseball video game you loved even more? Leave a comment below. And, as always, like, subscribe, and share with your old school baseball friends!

I ran a tournament last year in Toronto called the “King of Griffey”. It got a nice response so we’re doing another one this year on September 22nd.

I also run an online league. Lots of fun!

Greatest sports game ever! That 13-2 record is an anomaly. When we play, there is no way I am that much better! Have to say the Angels, Brewers and I hate to say, the Cardinals are my go to teams! Of course the Braves and Blue Jays are two of the best teams from top to bottom, but the White Sox might be the best all around team (defense,speed, pitching, hitting, power) in the game.