A power station currently stands on the site of my greatest baseball accomplishments. I’ve written about Murray Field before— the moniker I’ve given the yard beside my grandparents’ house— where my cousins and I spent countless afternoons living out our major league fantasies, but now the field itself only exists in the hazy realm of imagination and memory.

My grandparents moved in early 2001. Health problems were taking their toll on both of them, and the big two-story house, with a basement where we played darts and occasionally snuck a cigarette out of my grandma’s purse, had become too much for them to handle. At the insistence of my mom and my aunt, they decided to downsize and move across town to a more manageable house. My other aunt protested the move loudly— she does everything loudly— insisting that she wanted to buy the house, even though she didn’t have the money, and keep it in the family. She’s a total loon, but in this case, I wish she had gotten her way.

By the time they moved, the baseball field had long been out of use. My cousins and I had grown up and moved on to other things— some good, some not so good. Much to my grandfather’s relief, grass had finally been allowed to grow over the dirt patch we used for home plate. Standing at it as a grown man, the whole yard felt absurdly small. How had we ever imagined it to be an MLB ballpark? It seemed ridiculous, but we had. And once upon a time, the whole thing had felt majestic.

I moved to Chicago later that year. I remember it well, because it was the week following 9/11. What can I say? I’ve always had impeccable timing. I was determined to never come back to Kansas again. Like many of my grand plans in life, however, that didn’t work out the way I expected.

The house had long since sold by the time I returned. The new owner lived in it awhile, and then he got a job somewhere else and put the house on the market. It was up for sale for a long time. Nearly a decade after my grandparents originally sold it, I moved back to town with my own family. We rented a house down the street. I would have bought the old place if I’d been in any position to afford it, but I remember taking my sons for walks past it and peering in the dusty windows to catch a glimpse of something familiar. The whole experience was bittersweet.

I just wanted to go inside and take one last look around, but I never got the chance. My first marriage fell apart and I moved out of town again. Then the city bought the land and bulldozed my grandparents’ house and our old baseball field, and constructed the Amelia Earhart Substation and Commemorative Wall. I’m sure they thought were being creative with the wall depicting a timeline of Earhart’s accomplishments working as an aesthetic cover for a practical component of local infrastructure. In most cases, I might even agree with them. But I drove past it recently, and it will always be an eyesore to me.

The attachment we form with certain places can be incredibly powerful. Twenty years have passed since I was in that house and played in that yard, half my life, and yet it still feels as present as ever in my memory. And this got me thinking— if we can build these kinds of unbreakable bonds on a personal level with places that matter only to us, then how powerful must those same bonds be with a location of communal significance? I’m talking about a place that everyone is connected to, a building swirling with a mixture of private and shared recollections, where generation upon generation have walked through the doors and experienced exuberant joy and callous heartbreak and everything in between. A place like, say, a baseball stadium.

This topic has been front and center in Kansas City for the last year, ever since the Royals announced their intention to move to a downtown stadium within the next decade. Of course, this has given rise to the usual debates. Do they really need a new stadium? The K was just renovated a decade ago. Who’s going to pay for this stadium? Is it going to fall on the taxpayers? Do the Royals deserve this? They haven’t fielded a competitive team in years? Will a new stadium help them compete? If they don’t get their way, will the team move? Where is everyone going to park?

These are all relevant questions, and if you’re interested in answering them, I’m sure there are many other writers on Substack and other platforms who are willing to address them. But that’s not really my focus today.

I will miss Kauffman Stadium. Yes, it is fifty years old, but especially after the renovations made before the 2010 season, the stadium definitely doesn’t look its age. This is not an argument against building a new stadium, just an acknowledgment of the K’s charm and general upkeep. Most of the criticism of the stadium from out-of-towners is about its location, so far removed from the rest of the city, but few have any issues with the stadium itself.

With its iconic fountains in the outfield and massive Crown Vision scoreboard, Kauffman is a beautiful place to watch a baseball game. I’ve seen more games there than I can count, and with the possible exception of one incredibly hot afternoon in 2019 when the hapless Royals got shut-out by an uninspired White Sox team while I tried to wrangle a group of restless kids in the miserable heat, I’ve never had a negative experience. And I can’t even blame that one on the stadium.

I saw my first game there in 1985, and it was a life-changing moment. So much so that I wrote about it in my first article when I started this newsletter. Memories of other games are sprinkled throughout this website. I’ve seen championship teams and 100-loss teams run out of the dugout. I’ve watched All-Stars and Hall-of-Famers (only one in Royal blue though, at least until Zack Greinke is inducted), and a parade of league-minimum JAGs whose names I’ve long since forgotten. I’ve cheered the Royals, and on occasion, I’ve bought tickets based solely on the opponent.

Sometimes the place has been sold-out and packed to the light fixtures. Other times it’s been so empty I’m sure the players could hear the hecklers in the nosebleed seats. More often than not, it’s been somewhere in between. I’ve been in the seats for walk-offs, comebacks, blowouts, and rainouts.

I’ve watched games with my dad and my late mother, my cousins and aunts and uncles, two wives (the second being the love of my life), my kids, various friends, and innumerable strangers. And while I am by nature an introvert, even I have occasionally formed brief, intense friendships with a few of these strangers during a particularly exciting match-up. Baseball is one of the few things in this world that can get me to spontaneously high-five a total stranger.

That’s the power of baseball, and it’s why we tend to form such a strong connection to the places it’s played. I’m not a religious man, but Kauffman is as sacred to me as any church. In some ways, it’s like a home away from home. And just like when I’ve moved in real life, I’m excited by the prospect of going someplace new, but I know I’m going to miss the old place when I get there.

I think this is pretty common in most baseball cities. Perhaps we’ve cheapened that connection a little, both by replacing stadiums at a more frequent rate than ever before and especially by selling the naming rights to a never-ending carousel of corporate entities— certainly Guaranteed Rate Field doesn’t have the same ring to it as Comiskey Park in Chicago. But even that gripe might be overblown. After all, the Cardinals have played in Busch Stadium (two incarnations of it, in fact) for as long as I can remember. Call the park whatever you want— if people are living and dying with the team, the place will matter to them.

As a kid, my own experience was narrow and essentially limited to Kauffman. Other than a trip to old Mile High Stadium in Denver in 1993, I didn’t visit any ballparks outside of Kansas City until I was an adult. So, in a sense, I was lucky. If I was going to be limited to only one stadium through the first half of my life, I could have done a lot worse than the K.

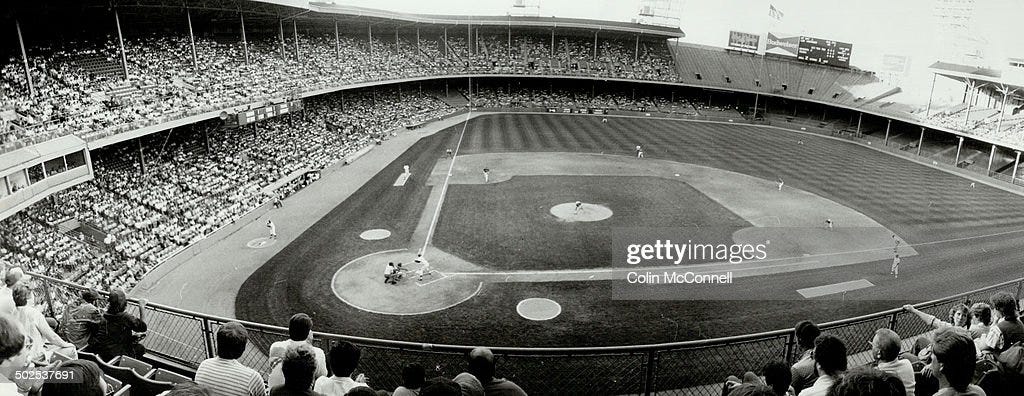

Kauffman Stadium was the only park built solely for baseball from 1966-91. Ewing Kauffman, drawing on Dodgers Stadium, wanted a unique ballpark with real character, and in this respect he succeeded marvelously. Most of the stadiums built during that era were cookie-cutter constructions used for both baseball and football, usually employing the standard “concrete donut” design. Prime examples of this include Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati, Three Rivers in Pittsburgh, and Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia.

Don’t underestimate these stadiums because of their generic design, however. I have no doubt that fans of those teams, who grew up attending games in those parks, feel as strongly about them as I do about Kauffman. Like any house, the occupants’ feelings on the general layout are only part of the story. What matters far more are the experiences they have within it.

Yes, the pictures might not look as pretty in the photo album, but the fans who watched the Big Red Machine dominate in Riverfront in the 70’s couldn’t care less. If I had grown up in Pittsburgh and watched the Pirates win back-to-back-to-back NL East titles from 1990-92, I’m sure that the mere mention of Three Rivers Stadium would fill me with warm, fuzzy feelings.

But there are two stadiums that I want to touch on real quick before I sign off for the day. I could probably single out more. For example, both Skydome (now Rogers Centre) in Toronto and Camden Yards in Baltimore come to mind as unique parks that jumpstarted the modern era of MLB stadiums. Both brought something original to the table— Camden was a nod to the past with its retro look and Skydome seemed to come directly from the future— and they marked a clear break with the “concrete donut” look. And as a testament to their viability, both are still in use. Then there are the many other domes, which probably need a write-up of their own.

For now, however, I want to focus on two relics of another era that have come and gone, but still hold a firm spot in baseball lore. Like I said, I never got the chance to visit either of them, but even through my television set, old Comiskey Park in Chicago and Tiger Stadium in Detroit made their presence felt, and I’ve never forgotten them.

Comiskey Park was my favorite. I always got excited when the Royals were playing on the South Side, because I knew it would look cool. And you know, in some ways, I got to know these distant parks even better than the K, because only road games were shown on local TV back then. So while I got the annual personal experience at Kauffman, thanks to TV and MLB’s ridiculous blackout policies, I visited other AL ballparks far more frequently.

Like I said, Comiskey was always a treat. Even my mom liked watching the White Sox play, though this probably had more to do with her being a big Carlton Fisk fan than the stadium itself. The White Sox had great uniforms back then, with the batter logo and numbers on the hip, and somehow their pants and jerseys always seemed to be an incredibly crisp white, even on our primitive 80’s televisions. But as a little kid, the stadium stood out to me even from afar.

Comiskey had these distinctive bright yellow railings that ran throughout the stands. I’m sure other ballparks had the same basic setup, but there was something about the way they were painted that made them stand out in the background on TV. My grandpa once said it looked like the fans behind home plate were in some kind of barricade. To me, they looked like the bars that go across your lap on a rollercoaster. It was like the fans were being strapped in for a ride at the ballpark, which always struck me as a cool sentiment.

I’ve never seen any other stadium in person or on TV that has given me that same impression. When the White Sox moved to their new stadium in 1991— first called New Comiskey, then U.S. Cellular Field, and now Guaranteed Rate Field— I remember feeling so disappointed the first time I saw it on TV and realized that aspect had not carried over to the new location.

The White Sox broke an 86-year long drought and won a championship in their new place in 2005, and I’m sure new generations of Sox fans view the park in a positive light, but few places can match Comiskey’s position in baseball lore. Named after original Sox owner, Charles Comiskey, who was both pivotal in the development of the American League and so cheap that he indirectly inspired the 1919 Black Sox scandal that tarnished his franchise, its overall legacy is both as famous and infamous as its namesake.

Pinwheels above the outfield scoreboard turned whenever a White Sox player homered, accompanied by fireworks, and Comiskey had a mixture of energy and griminess that contrasted nicely with the ivy of Wrigley Field on the North Side, and accurately defined its team’s reputation in contrast to the more upright Cubs. This was the place where a riot broke out during the ill-conceived Disco Demolition Night in 1979, and also where legendary owner Bill Veeck first encouraged Harry Caray to sing “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” during the seventh inning stretch. The latter took the tradition with him when he jumped to the Cubs, but Comiskey was where it started.

Tiger Stadium in Detroit had the same kind of down and dirty feel about it, even if it wasn’t quite as boisterous. Recently, I listened to an interview with one-time Royals broadcaster Dave Armstrong, who retired from announcing this past year. He was better known for calling college basketball games, but when asked about the most meaningful moments of his career, he immediately recalled a story from his brief time with the Royals.

On a road trip to his hometown of Detroit, he was given the opportunity to shag fly balls during batting practice. Standing in the same spot he had watched his boyhood hero, Al Kaline, play, he got goosebumps and shared his thoughts with George Brett. Brett concurred, pointing out that it wasn’t just Kaline. The two of them were standing in the footprints of greats like Ty Cobb, Hank Greenberg, and even Babe Ruth. (Ruth was obviously a Yankee, but played many road games in Detroit.)

Those are the kinds of ghosts that inhabited Tiger Stadium. And though they might not be ghosts yet, Tigers fans of my generation got to watch players like Lou Whitaker, Alan Trammel, and Kirk Gibson play on that field. We watched Cecil Fielder and a visiting Mark McGwire blast homeruns that actually went over the roof that hung above the distinctive left field bandstand and leave the stadium. Along with Harmon Killebrew and Frank Howard, they’re the only four players to ever do that, though over thirty moonshot dingers were hit onto the opposite field roof in right. It was a ballpark built for slugging.

Few ballparks represented the golden age of baseball better than Detroit, which perhaps explains why so much of an effort was put forth to preserve it after it closed in 2001. Comiskey was torn down and turned into a parking lot for the new stadium— a marble plaque marks the location of home plate under the cars— and even old Yankee Stadium, the “House that Ruth built” was razed without much protest. But people fought to keep Tiger Stadium standing.

Not just hardcore baseball fans either. In 2004, I worked at a bookstore in Lawrence, Kansas. One of my co-workers, a twenty-something lesbian sci-fi nerd with a moderate Elliott Smith obsession, had a bumper sticker on the back of her old Buick that said SAVE TIGER STADIUM. I never heard her express any interest in baseball, and to my knowledge, she had no connection to Detroit. I never found out why she had the sticker. Maybe she was just really into historic preservation. More likely, she was a bit of a hipster. Not that it really matters. The point is, a lot of people wanted to save Tiger Stadium.

Alas, their efforts were for naught. The place fell into disrepair and demolition began in 2008. Perhaps this was for the best, but even now it’s still a bitter pill to swallow. Thinking about it fifteen years later, I can’t help but recall my own childhood home, which is still standing in rural Kansas, albeit barely. The place has been abandoned for a decade, and the last time I drove out there it was in bad shape. Windows were broken out, the grass was knee-high and had reclaimed the driveway, and a tree had fallen over in the front yard, blocking the porch.

I was surprised by how sad this sight made me. This was the house where I had spent the first half of my life. So much of my identity was tied up in that building. It didn’t seem right that it had been left to rot and eventually collapse. Compared to the fate of my grandparents’ house and our old ball field, this felt even worse. As much as I hate that power station, at least their house and Murray Field stand pristine in my memory, and I never had to witness their cruel decline. But my own home? Nothing but ruins.

It may not seem like that big of a deal. There are obviously far bigger problems in the world. But I still wouldn’t wish that feeling on anyone, especially the baseball team I love. I’ve heard baseball stadiums be compared to cathedrals, and I don’t think that’s far off the mark. They’re a place we congregate together to experience bliss and agony, serenity and mania. We commune with higher powers in those seats, and sometimes we lose faith altogether. Mostly, we just try to work through whatever the game throws at us and find a few hours of happiness. There’s something beautiful and sacred in that, and nothing sacred should be allowed to rot.

One day, Kauffman Stadium will be gone, just like Comiskey and Tiger Stadium and even Murray Field before it. Nothing lasts forever, after all. Except the ghosts.

They’ll still be running the bases long after the fences have been plowed under.

Thanks for reading Powder Blue Nostalgia. What baseball stadium served as your “church?”

Terrifically memory-tugging, Patrick! I was 10 when this native Houstonian first set foot in the Astrodome in 1965, when it debuted! I remember, still, the sight that unfolded as I trundled up the ramp to our seating section. The roof was astounding to see after 3 years lugging, with my folks, blankets, cans of Off!, and other anti-humidity accoutrements to Colt Stadium!

In December 1965, I saw The Supremes open for Judy Garland, and in '68, I not only saw Jim Wynn hit 3 "Domers" in one game, and in another game, I caught my first (and only) foul ball, off the bat of Giants 3B, Jim Davenport! Here's an article I wrote in 2014, one of my first for The Runner Sports....it's as close as I can come to an actual testimonial for a building! https://therunnersports.com/houstons-astrodome-is-50-hats-off-to-the-grande-dame/ Hope you enjoy as much as I enjoyed this one!

I grew up going to Comiskey, and it was awesome - thanks for sharing your TV perspective. Nancy Faust's organ was great too! Even if you had bad seats, and couldn't see the ball when it was hit in the air, the crowd was so much louder when it's tucked under a roof or upper deck. Once I could see the pitcher and catcher, but a pole was in between! I wish I had visited Tiger Stadium once. If I had a time machine to see one game at an old ballpark, I'm torn between visiting Tiger Stadium for the first time or my ninth game at old Comiskey.