I’m gonna be honest here. While there is a part of me that is ambitious and wants to accomplish something noteworthy during my time on this planet— and I don’t think I’ve done too bad on that end; I’ve got a wife and three sons, a career, I’ve written at least one good novel, published several short stories, started my own baseball newsletter, and I’m not done yet— there is another part of me (probably a bigger part than I’d like to admit) that has never wanted anything more than to immerse myself in the relaxed lifestyle of my retired grandparents.

Even as a ten-year-old kid, I was envious of them, despite the fact that as a child I probably had even less on my plate than them. I spent a lot of time at my grandparents’ house as a kid, especially during the summer, and compared to my parents, who worked long hours at demanding jobs they didn’t particularly care for in exchange for a paltry payoff, my grandparents had it made. Or, at least, that’s how it looked to me.

My grandma was a retired educator, and she spent most of her days sitting at her big dining room table, chain-smoking cigarettes and drinking coffee, reading mystery novels and doing crossword puzzles. My grandpa’s routine was even better. He rose early, read his Louis L’Amour westerns, watched old movies or reruns of cop shows from the 70’s, and whenever he felt restless, he went for a drive and picked up his lottery tickets. And, of course, he watched a lot of sports.

Some of my best sports memories were watching games with him. He was knowledgeable about baseball, basketball, and football. (Golf too, but I never really cared about that.) A tall man, he had a scholarship to play basketball in college. Nothing too big-time— it was for a local community college, not UCLA— but World War II interfered, so we’ll never know if it could have gone anywhere. But he taught me a lot about sports in that living room, and it was through him that I started to gain an understanding of the history surrounding the games I loved.

I watched my first Super Bowl with my family gathered around his TV, and the vivid memory of the ’85 Bears dismantling the Patriots has stuck with me all these years. I’ve been a Notre Dame football fan since I was ten years old, but he hated the Fighting Irish, and especially Lou Holtz. (Many years later, it’s become abundantly clear that he was right about Holtz.) To emphasize his distaste for Notre Dame, he used to tell me stories about Army kicking their ass back in the 40’s. He was my first introduction to the legend of Mr. Inside and Mr. Outside. When I gushed about Danny Manning and other contemporary players for my Kansas Jayhawks, he gave me his firsthand appraisal of Wilt Chamberlain. (Long story short: he was really good.)

No sport has more history than baseball though, and whenever we watched baseball in his living room, he was more than willing to give me a crash course on the greats who had come before my time. Certain names, in particular, stand out from his lessons. Joe DiMaggio. Mickey Mantle. Yogi Berra, as much for his stories and wisecracks as his skill behind the plate. Sandy Koufax. Stan Musial. Bob Gibson. Willie Mays. Jackie Robinson. It’s interesting that while my grandfather definitely possessed a streak of old school prejudice that was far too prevalent in his generation, I never heard him direct toward it toward any of the great black ballplayers I listed. This hypocrisy has always confounded me, but if I were trying to put a positive spin on it, I suppose it is proof that baseball is capable of leading the way in the struggle against racism, even if only by taking very small steps.

I loved watching baseball with my grandpa, and thankfully there was never any shortage of games to choose from. Of course, Royals games always took top priority, but unlike my parents, my grandpa had cable. This meant that ESPN was on the table, along with several other options.

The Braves were on TBS, a phenomenon I’ve written about before. I loved Skip Caray and the TBS broadcast team, and it was awesome to watch the Braves go from perennial doormat in the 80’s to powerhouse in the 90’s. The whole “America’s Team” label was just a marketing slogan from Ted Turner, but as the Braves transformed from lovable losers to baseball titans, I think it started to have a ring of truth to it. But today I want to talk about the team that played on the other Superstation, WGN.

The Chicago Cubs were also often looked at as lovable losers, but unlike the Braves, they’ve never really done anything to shed the label. Sure, they’ve had some great players and teams— the Cubs won the NL East in 1984 and 1989, though they fell short of the World Series on both occasions— and even after breaking a century long curse and winning the 2016 World Series, the Cubs are still generally viewed as chronic underachievers. But the Cubs have always had one thing that no other modern baseball team has. Or at least they did. Much to the chagrin of baseball traditionalists everywhere, especially in the Windy City, it’s becoming less pronounced every season.

The Cubs play day baseball. At least, they play a lot more day games than other teams. Sure, most teams play day games on Sundays, and they tend to mix in occasional Saturday afternoon games. During the week, it’s not uncommon for teams to play semi-regular early games on a Wednesday or Thursday. These are generally the final game of a series and are called getaway days for the home team. The early start and finish buys them a little extra time before they hit the airport for a road trip that evening. Beyond that, night baseball is now the norm.

In her book, Why Baseball Matters, Susan Jacoby addresses several issues she views as the biggest threats to baseball’s prosperity and ultimate survival. Marketing the game, especially to younger fans, is one of the primary problems she zeroes in on. Before the cranky old men in the back start griping about how they shouldn’t have to change the game they love to accommodate kids with short attention spans, there are several approaches MLB could take to help with this problem without ever touching the game itself. First and foremost, is play more day games. Unfortunately, MLB is generally terrible at this sort of thing.

Day games used to be more common. I mean, night games serve a purpose, of course. A lot of people work during the day, so it makes sense to schedule games when more people can attend or watch on TV. But kids are out of school in the summer, not everybody works 9-5, and there is no shortage of people who are willing to take a day off to head out to the park. Or there didn’t used to be anyway. Hell, they used to play the World Series during the day (before my time) and teachers used to let the students watch/listen the same way my teachers let us watch NCAA tournament games.

Nowadays, the World Series (and really most baseball) is in prime time, because that’s where the advertising dollars are. Even the national game of the week is aired on Saturday nights now, instead of the afternoon like when I was a kid. I liked to fall asleep listening to baseball on the radio, but those were relatively unimportant regular season games. World Series games often don’t even start until after the youngest fans’ bedtime, and I would guess most kids never make it to the ninth inning.

Game 1 of the 2015 World Series went 14 innings. I don’t remember what time it actually ended, but I was a full-grown man (and a bit of a night owl, at that) and I was fully engaged as my team, the Kansas City Royals, was competing, and even I struggled to stay awake until the game’s finish. I had to work early the next morning, had moved from the couch to the TV in my bedroom, and was quickly nearing the point where I didn’t care who won the game, just as long as it ended soon. Fortunately, Eric Hosmer walked it off with a sac fly before I got to that mindset, which is something no die-hard fan should ever even be contemplating when their team is playing in the World Series.

MLB has acknowledged this problem in recent years, but in typical MLB fashion they’ve addressed it in a half-assed fashion. Speeding up the game helps a little, and many teams have moved up the first pitch for weeknight games by a half-hour or so. For example, weeknight games at Kauffman Stadium usually start at 6:40 now, as opposed to 7:10. But the league, as a whole, has resisted the idea of adding significantly more day games.

Sunshine was part of the Cubs’ allure, however. They were the one team that actually played day baseball. In fact, when I first started watching baseball in the mid-80’s, the Cubs didn’t have any choice in the matter. Wrigley Field, the second oldest stadium in baseball (after Fenway in Boston), with its iconic ivy covering the brick walls in the outfield and North Side locale, didn’t have lights until 1988.

It's hard to explain how big of a deal this was to me (and many others) back then. I hated when the Cubs were on the road, because having a regular afternoon baseball game to look forward to instead of the usual boring fare of reruns, soap operas, and talk shows was priceless. After eating lunch— my maternal grandmother wasn’t much of a cook, so it was usually something simple like a sandwich— I’d head out to the side yard/baseball field. If I was by myself, I might throw the ball up to myself and take some batting practice. Or maybe I’d act out some highlights in the field. If my cousins were there, we’d start a game, play a few innings, and then beat a retreat from the heat to grab a glass of lemonade and take a quick break.

Generally, we’d try to time this for around one o’clock, because that’s what time my grandpa would be flipping the TV over to WGN for the start of the Cubs game. The iconic and incomparable Harry Caray greeted viewers as only he could, and was joined by the understated and underrated Steve Stone in the booth. The two of them discussed the keys to the game and shared the Cubs’ starting lineup, which generally included stars like Ryne Sandberg, Andre Dawson, and Mark Grace.

Those guys are kind of my holy trinity of Cubs. I’ve written about Dawson before in relation to his time with the Expos, but I remember the Hawk primarily as a Cub. His knees were always a question mark, but his 1987 NL MVP season was special to watch, and I was impressed by his ability to match Mark McGwire (who was already becoming one of my favorite players) dinger for dinger for the 1987 MLB home run crown.

Ryne Sandberg was the 2B for me growing up. The only guy who even came close, in my opinion, was Lou Whitaker in Detroit, but I saw more of Sandberg’s prime and he was arguably better overall anyway. Of course, I was quite partial to Frank White as a Royals fan, but White, while second to none as a defender, was just an average bat. Sandberg was the total package. A perennial All-Star and 1984 NL MVP, he owned the position during my formative years, even if the quality of his team rarely measured up to his individual talent. Plus, he had one of the coolest names in baseball. It was Ryne, not Ryan. How could you not be a Ryno fan?

Then there was Mark Grace, one of the most consistent and undervalued players of the 90’s. In fact, if you’re looking for a good trivia question, Mark Grace had more hits than anyone else in baseball during that decade. A cornerstone of the Cubs at 1B, he never had the flashy power of his peers, McGwire or Cecil Fielder, but he played in three All-Star Games and won four Gold Gloves.

They weren’t the only Cubs players to make an impression on me during those summer afternoons, though it would take too long to list them all. Shawon Dunston (another guy with an unusual first name) was one of those can’t-miss prospects who didn’t exactly miss, but didn’t live up to the hype either. Rick Sutcliffe was a very good pitcher with local ties to Kansas City, and WGN gave me my first exposure to legendary closer Lee Smith. The same is true of Greg Maddux, probably the best pitcher I’ve ever seen, even if he would move on from the Cubs after 1992 and have just as many, if not even more, glory days for the Braves on TBS. And there was some guy named Sosa, who became a superstar in the 90’s and left behind a rather complex legacy.

I’m not saying these players wouldn’t have made a similar impression if they’d played most of their games at night. The Braves of the same era are proof of the superstation effect, regardless of what time of day the games were played, but I won’t argue that it didn’t matter. The day games set them apart from everyone else, and made Cubs baseball special, giving them a unique identity in Major League Baseball.

The players may not have always agreed with me— a lot of them enjoyed having their evenings free, but Rick Sutcliffe claimed that he once lost fourteen pounds pitching a complete game during the heat of the day at Wrigley— but I’m glad they resisted the urge to install lights for as long as they did.

It almost didn’t happen. Cincinnati was the first MLB team to install lights for night baseball in 1935. The rest of the league gradually followed their lead, and the Cubs were scheduled to do so in 1942. Pearl Harbor put those plans on the back burner. The steel they planned to use was sent to the Navy for use in the war effort, and even after the war ended, lights on the North Side remained a low priority. Instead, the Cubs embraced the idea of being traditionalists, though this was likely just a convenient cover for being cheap and not wanting to spend the money on lights.

The Tribune Company bought the Cubs in 1981 with the idea of making money and winning games. The former was probably always their top priority, and to the people in charge that meant night baseball. They were met by surprisingly stiff resistance, however, in the form of C.U.B.S.: Citizens United for Baseball in Sunshine. This was a group of Wrigleyville residents concerned that noise and traffic issues in the neighborhood would get even worse if there were night games. I’m not completely sold on their logic, and I also find it funny that a neighborhood whose whole identity is built around Cubs baseball and the partying that accompanies it would have such a problem with doing it a few hours later in the day, but that’s what the Cubs were up against.

C.U.B.S. staged rallies, passed out shirts, and took their case all the way to the state legislature, effectively getting their way for years. Things got serious in 1984 though, when the Cubs won the NL East pennant. MLB did not like the idea of losing prime time revenue during the World Series, so even though the NL was scheduled to have home field advantage (it alternated at the time), a deal was struck to alter the schedule. If the Cubs won the pennant, they would sacrifice home field advantage so MLB could schedule Games 3, 4, and 5 around a long weekend, minimizing the hit they would take broadcasting World Series games during the day.

It was obvious that TV was calling the shots now, though it came to nothing since the Padres beat the Cubs in the NLCS and made the point moot. The following season, however, the Cubs were in contention again, and new commissioner Peter Ueberroth toyed with the idea of moving Cubs home games to an alternate site if they made the playoffs. Ultimately, it came to nothing again, as the Cubs failed to win the East, but it was apparent something needed to be done.

In 1988, the Chicago city council voted to allow eight home games that season, and eighteen for future seasons. The shortened Covid season of 2020 was the first to allow for weekend night games at Wrigley, and the current agreement allows for forty-eight night games a year. So it has seen quite the jump.

Interestingly enough, there are actually two first night games in Wrigley Field history. The first took place on August 8, 1988. It was quite the big deal. I wasn’t able to watch it, but I remember the build-up to the game. Sutcliffe, who started the game for the Cubs, compared it to a World Series environment and called it the biggest event of his career.

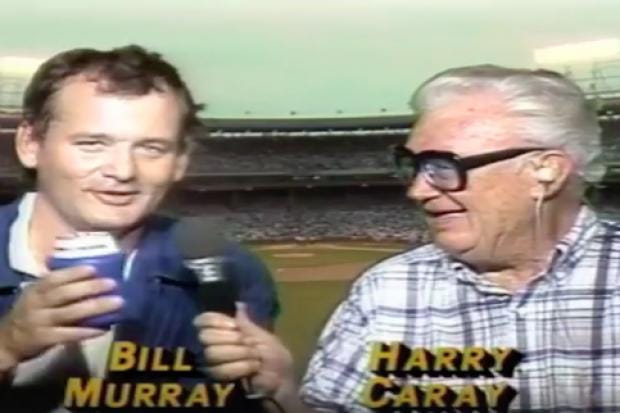

All the broadcasters on WGN wore tuxedos, except for Harry Caray. He wore his normal short sleeve button-up shirt and shared a Budweiser with Bill Murray, who joined him in the booth before the game. Murray admitted that he wasn’t sure about night baseball, but everyone seemed to be having a good time.

The Cubs were up on Philadelphia, 2-1, on a Sandberg home run when the rain hit in the fourth inning. They didn’t dare cut away to an Andy Griffith rerun, which was their standard operating procedure, so Harry interviewed all the celebrities in town for the special occasion while Greg Maddux and other Cubs treated the tarp like a Slip n’ Slide. Eventually, the game was called before it was official.

That set the stage for the first night game at Wrigley, take two. Taking place the following night, the game between the Cubs and Mets was scheduled for a national broadcast on NBC. This meant that Vin Scully and Joe Garagiola were on the call. Now, Scully is arguably the greatest announcer in baseball history, and he and Garagiola were an all-time great combo in the booth, but there’s just something wrong about them being on the mic for this moment. Any momentous Cub moment of that era should have been on WGN with Harry Caray and Steve Stone on the call. But that is how Vin Scully, not Harry Caray, called the first official night game at Wrigley Field. The Cubs beat the Mets, 6-4.

Looking back, I’m not sure how I feel about the moment. At the time, it was hard not to get caught up in the novelty of it. This was something new, and it felt like the Cubs were finally getting with the times. But in retrospect, I kind of wish they hadn’t. WGN doesn’t even air Cubs games anymore, and as I mentioned earlier, over half of their home games are now night games. We definitely lost something along the way.

I lived in Chicago for about a year in 2001-02. I moved three days after 9/11, but that’s a story for a different time. I lived on the North Side, but baseball wasn’t a high priority for me at the time. It also didn’t help that I was painfully broke most of the time I lived there. I didn’t attend a single game while I was a resident, an oversight I would come to regret, but I did spend a fair amount of time in Wrigleyville. The neighborhood had a bookstore I liked, and several good places to eat. Of course, I had to grab a “cheezborger” at the infamous Billy Goat Tavern. Wrigleyville is a world of its own on gameday, and I encourage everyone to check it out whether they ever buy a ticket to the stadium or not.

I finally saw my first live Cubs game in 2022, during a family vacation. Wrigley was everything I dreamed it would be, and now occupies a hallowed part of my baseball heart. And the best part was that I got to experience it with my wife and three sons. The Cubs won 2-1 on a dramatic Wilson Contreras home run in the bottom of the eighth. In an eerie connection to the first official Wrigley night game, the great Vin Scully had passed away a few days earlier and they played a video him singing “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” during the seventh inning stretch. Most importantly, it was a day game on a Friday afternoon.

The sun was shining on Cubs baseball at Wrigley Field, just like it always should.

Thanks for reading Powder Blue Nostalgia. Big news, next week PBN will be getting a bit of a makeover. I’m streamlining it a bit. Long story short, it’ll be shorter, but you’ll still get your weekly fix of vintage baseball. In the meantime, I invite you to subscribe if you haven’t already, and leave your thoughts on the lights going on at Wrigley in the comments below.

I remember a lot of jokes about God preferring day baseball, hence the rainout of the first attempt at night baseball at Wrigley.