All-Star voting begins today, but before you do that, why not show your support for Powder Blue Nostalgia by hitting the like button and subscribing, if you haven’t already? All it takes is a single click to get retro baseball delivered straight to your inbox every week.

The NFL finally put the Pro Bowl out of its misery this year. The mercy killing was long overdue. Football’s all-star game had become a glorified walkthrough of a touch scrimmage. Half the elected participants didn’t even bother to show up.

You couldn’t really blame them. As athletes have gotten bigger, stronger, and faster, the risk of injury in such an inherently violent sport has only increased, despite whatever efforts the league has made to bolster player safety. Sure, the bulk of professional football players are more than willing to risk their short-term and long-term health for big paychecks in games that count, but for an exhibition game? Not so much.

The quality of the Pro Bowl wasn’t as bad when I was a kid, but even for a sports-obsessed kid like myself, it was hardly appointment viewing. I mean, the fact that it was on ESPN and we didn’t have cable meant that I usually missed it by default anyway. I didn’t really care. The Pro Bowl wasn’t something I was going to make special arrangements to watch.

The NBA All-Star Game has always been more entertaining, but it has never felt truly special in its own right either. It can be a lot of fun seeing the greatest players in the world on the court together at the same time, and the nature of the sport gives the athletes an opportunity to highlight their skills for the audience.

Unfortunately, those efforts usually only apply to offense. Players indulge in showboating moves they would never risk in a game with real stakes, flashing behind the back passes, alley-oop lobs, and all sorts of gimmicky dunks. No one ever expends much effort on defense, so the floor is wide open for all sorts of jaw-dropping displays.

The final score never matters much. If anything, the game feels more like an extension of the weekend’s other festivities than an actual competition. The slam dunk contest was a big deal when I was younger, though it’s lost a lot of its mojo in recent years. As the three-pointer has risen in prominence over the last decade or so, the three-point contest has supplanted the dunk contest as the top draw, and the recently revamped skills competition continues to grow in relevance. The NFL’s new Pro Bowl Games appears to have taken notice, and it seems like they will attempt to copy this format in its efforts to celebrate its all-stars moving forward.

The MLB All-Star Game has always felt different though. Marking the symbolic middle point of the season— usually scheduled on a Tuesday in mid-July, the game is generally played slightly after the mathematical mid-point of 81 games— baseball’s midsummer classic has traditionally mattered to both players and fans, despite the fact that it has been a true exhibition game for most of its storied history.

The exception to this was between 2003-16, when the winner of the game between the American and National Leagues decided homefield advantage for that season’s World Series. This came about after the 2002 All-Star game in Milwaukee was called after eleven innings with the score tied 7-7, because each team had exhausted their entire bullpens. Commissioner Bud Selig, the former Brewers owner, saw one of his crowning achievements (hosting an ASG in Milwaukee) go up in smoke as he made the controversial call from his seat in the park, drawing an incensed reaction from the crowd around him.

Sensing that enthusiasm for the All-Star Game might be slipping and going the way of the Pro Bowl and NBA All-Star Game, he announced the added stakes the following season. Baseball purists threw a fit, like they always do (for better or worse) whenever the slightest tweak is made to the game, but I’m not going to lie— I had no problem with the change.

Okay, I didn’t love the idea of the ASG determining homefield advantage in the World Series in principle, but I had always enjoyed the All-Star Game and I could sense the apathy seeping into it. I was all for anything to combat it. Plus, at the time of the rule’s introduction, it seemed unlikely that it would ever have any impact on my Royals. What were the odds they were ever going to make a World Series run anyway? Fortunately, the AL won both the 2014 and 2015 All-Star Games, giving Kansas City homefield for both of its unexpected World Series appearances. They went 1-1, by the way, so homefield advantage ain’t everything.

New commissioner Rob Manfred changed the game back to a pure exhibition in 2017, and I do have concerns about its long-term future. And perhaps not surprisingly for a newsletter that takes its name from a uniform trend, my biggest problem with the modern ASG is that they have recently adopted game-specific AL and NL uniforms.

One of the coolest things about the ASG used to be seeing the players take the field in their own mismatched team uniforms. Don’t ask me why this is such a big deal. I can’t properly explain it to someone who hasn’t lived and breathed baseball, but trust me when I say I’m not the only one bothered by this recent development. The impetus behind it is to sell more merchandise though, so I doubt it’s going away anytime soon, no matter how much we complain.

Uniform issues aside, the MLB All-Star Game is still special, even if the in-game strategy isn’t quite as sharp as in the past, and the battle lines between the AL and NL aren’t as staunchly drawn. In fact, that’s probably the biggest difference in the game between now and when I was a kid. Prior to the introduction of interleague play in 1997, the only other time most of these guys matched up against any of the players in the opposing dugout was if they were both fortunate to reach the World Series.

I think this mattered as much to the players as it did to the fans. AL and NL pride were real things back then, and unless they were lucky enough to reach the World Series, which was always a statistical long shot for even the best players on the best teams, this was the only shot most of them would get to prove their league’s superiority. Growing up a fan of an American League team, I always rooted for them. And because ASG results are often streaky, for reasons I cannot explain, the latter half of the 80’s and early 90’s were a good time to be cheering for the junior circuit.

The nature of the game of baseball plays a role in its All-Star Game’s success as well. This is not to say that fluke injuries can’t occur or that playing the game full-speed doesn’t occasionally lead to dangerous situations. Anyone who has seen the footage of Pete Rose trucking Ray Fosse at home plate to score the winning run of the 1970 ASG can attest to this fact. But on the whole, baseball doesn’t require the commonplace violence of football or the nonstop action of basketball.

This means that baseball players are more likely to give maximum effort, even in a game that doesn’t really count. A pitcher ratcheting up his delivery to full power isn’t that big of a deal, especially if they’re only going to be out on the mound for an inning or two. The same for an infielder extending for a hard-hit grounder, or an outfielder attempting a diving catch. Like I said, the MLB All-Star Game matters, and Pete Rose charging the plate in 1970 is proof that one great play can live forever, even if the end result of the game doesn’t ultimately matter much.

And, of course, everybody likes to hit, regardless of the circumstances, and a clutch hit is the surest path to either the MVP trophy or ASG immortality. Oftentimes, the two go hand in hand. Take, for example, two of my favorite All-Star memories from the PBN era.

The first came in 1987. The two leagues had dueled to a scoreless tie through twelve innings. In the top of the 13th, Oakland A’s reliever Jay Howell allowed two baserunners while recording the first two outs of the inning. He nearly worked his way out of trouble, when one of my favorite players ever, Expos OF Tim Raines stepped into the box and laced a two-run triple to left-center. With Vin Scully on the call, the NL took a 2-0 lead and held on for the victory.

Two years later, Vin Scully was on the mic again, this time joined by former president Ronald Reagan at the Big A in Anaheim, when Bo Jackson announced his official arrival as an MLB star by blasting a leadoff home run. I’ve written about this Bo moment before, and while we all know that his potential would eventually be derailed by an injury before he could reach his ceiling, it was an awe-inspiring baseball moment that still feels impressive over thirty years later.

Phillies 3B Mike Schmidt was at that ASG as well, though he didn’t play. Schmidt, arguably the greatest player to ever man the hot corner— I hate writing that as a George Brett diehard, but I can’t deny facts— abruptly retired just 42 games into the 1989 season. He didn’t feel it was fair to the game or the fans to keep running out there when the game had passed him by and his passion was fading. The fans voted him in as an All-Star Game starter anyway. And while no one would have held it against him if he’d wanted to dress for one last game, he showed true class by stepping aside. He did come out for the pregame festivities, however, taking a well-deserved curtain call.

The relationship between the fans and the players is what makes the All-Star Game special, and why I hope its place in the sport is never truly diminished. At its best, the game serves as both an acknowledgement of the players’ abilities and a gift performance from the sport’s best to its fans. That connection, which MLB has not done a terribly good job of fostering in recent years, should never be underestimated or taken for granted.

Need proof? My first voting experience was at a MLB park. I’d never been given that kind of voice before, especially concerning something I loved. Nowadays, anybody can hop on their phone and vote over and over, but when I was a kid, you had to go to a game during a specific stretch of the season in order to get a paper ballot. I’m not saying one way was better than the other, but the old way did feel a bit more exclusive and special. So maybe the current method is actually more democratic.

Neither method was immune to abuse and ballot box stuffing. In 2015, Royals fans caught a lot of flak for going overboard with their votes. At one point in the process, Royals players were leading the vote count to start at eight different positions for the AL team. The most notorious offender was 2B Omar Infante, who lost his position due to injury and ineffectiveness early in the season. But you can usually tell if someone was a Royals fan in 2015 if the hashtag #VoteOmar is familiar to them.

In the end, the voting evened out a bit and only four Royals were voted into the starting lineup, though Alex Gordon was hurt and didn’t play. Three more were added to the bench, and Ned Yost, as the manager of the defending AL champion Royals was the AL skipper. If anyone feels like that was overkill, I will offer the fact that the Royals won the World Series that season as a defense. They were pretty good.

But as I said, similar stuff happened with the paper ballots as well. In 1988, the wrath of the baseball world was directed at Oakland fans, who were criticized for voting Terry Steinbach in as the AL’s starting catcher. His numbers might not have warranted it, but he silenced his doubters by driving in both AL runs with a home run and sacrifice fly on his way to the MVP award.

I, for one, won’t criticize anybody for being a homer on their ballot. As a Royals fan, I went through a lot of years where the Royals didn’t have a true All-Star on the roster. Each team is required to have one representative, however, even if they’re just a token addition. In the late 90’s and early 2000’s, outside of Mike Sweeney’s appearances in 2000-03 and 2005, the Royals’ lone no-name player often didn’t even get into the game.

I couldn’t blame the managers, but it was quite the comedown from my early All-Star Game experiences that featured stalwarts like George Brett, Dan Quisenberry, Frank White, and even Willie Wilson. That’s why it was so much fun to see guys like Salvy and Hosmer (the 2016 ASG MVP) become regulars in recent years.

On the whole, I’ve always tried to balance my fandom with my overall appreciation for the game when it came to filling out my ballots. Of course, I’d love to see more Royals in the game, and there is plenty of proof that even very ordinary players are capable of putting together great seasons worthy of ASG inclusion. Take Von Hayes, who made the ASG for Philadelphia in 1989 and was once labeled the next Ted Williams. He obviously didn’t make it anywhere near Ted Williams territory before he flamed out, but he is an All-Star Game footnote. Same with Vance Law, the Cubs’ 3B in 1988, and even Kurt Stillwell, who had his one standout season at shortstop for Kansas City the same year.

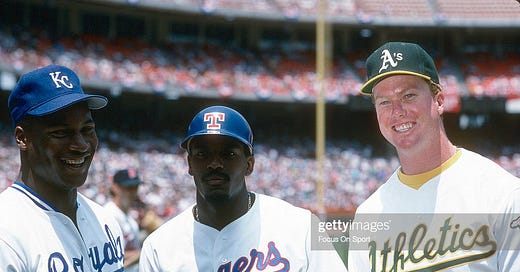

That said, the rosters for both the AL and NL were fairly static throughout most of my childhood, and deservedly so. It would take too long to list them all, but even the most casual fan could confidently pencil in certain players at specific positions almost every year.

George Brett made every ASG from 1975-88, locking down the starting 3B spot for the AL through 1985, when he passed the torch to Boston’s Wade Boggs, who became every bit the regular his predecessor was. Similar to his ironman streak in regular season play, Cal Ripken was an all-star every year from 1983-2001. Rickey Henderson and Ken Griffey Jr. were staples in the AL outfield, and Ryne Sandberg and Ozzie Smith owned the NL middle infield. And I can’t forget Tony Gwynn in the NL outfield.

This doesn’t even include semi-regulars who didn’t make it every single year, but were still regular participants, like Keith Hernandez, Paul Molitor, and a bevy of Hall-of-Fame caliber pitchers whose ASG selections were more erratic, based on early season smaller sample sizes.

In the end, I don’t think it mattered much whose names were scrawled on the lineup card. The one thing you could count on was that they would be at the top of their game and they would put on a show worthy of our attention. That’s why I went out of my way to catch the game on a yearly basis.

I always tried to watch it with my cousins. Sometimes we arranged to meet up at our grandparents’ house. We’d play a version of the game ourselves in the yard, then go inside just in time to see the player introductions and gauge the crowd’s reactions to each player. My grandma usually provided Country Time lemonade and a well-stocked candy dish.

More often than not, we wound up watching the game at my cousins’ house. This was mostly due to our little league schedule. Sometimes this meant we might miss the introductions or even the first inning or two, depending on how late our games went. I only remember getting caught playing the late game once on All-Star night, and even then we were still able to catch most of the second half of the game.

After our games wrapped up, my mom would drive me to my cousins’ house, since it was closer to our ballpark. We’d gather in the side yard with our glass bottles of Gatorade and ice pops, and the other neighborhood kids meandered over after they got home from the park as well. We’d BS about the games we’d just played, maybe sneak in a few rounds of hot box, and then my cousins and I retreated inside to the comfort provided by the blaring window unit air conditioner. Man, nothing ever felt as good as the frigid air blowing out of that thing on a scorching summer day. Then, while my mom and her sister talked on the couch, we’d stretch out on the floor and watch our idols do what they did best.

If you can come up with a better way to spend a Tuesday in July, I’m all ears.

Thanks for reading Powder Blue Nostalgia. Got any ASG moments you want to share? Highlights of specific games? Memories of how you watched the games? Or who you watched them with? Or something else entirely? Leave them in the comments below, and don’t forget, #VoteOmar.

You know Royals Fans are legit when they almost single handily got Omar Infante into the all star game

I had it rough growing up in Chicago. My grandpa was a Reds fan. Since my parents could care less about baseball I became a Reds fan. So as a kid I became a White Sox fan. The only problem was we lived on the north side of the city and all my friends were Cub fans. To make matters worse my highschool, Lane Tech, was right down Addison Ave from Wrigley Field.

I'm retired now and live 90 miles from Cincinnati in Kentucky. My hope before I watch my last game was to see a Reds White Sox world series.