Baseball can be a metaphor, a kind of stand-in for other aspects of life and the human condition. Or it can just be escapist entertainment. We can relax and roll with the results of any game or season, or we can take it entirely too seriously. I recommend the former, but it’s a game and we can all participate in whatever degree we see fit. But no matter how you see it, baseball is no more immune to death and tragedy than anything else in this world, whether we like it or not.

This was most recently hammered home to me in the winter of 2017, when the news came over the radio and social media that Royals pitcher Yordano Ventura had been killed in a car accident in the Dominican Republic. I was on my way to pick up my older two boys when I heard the news, and in addition to sadness, I couldn’t help recalling that Ventura had pitched for KC in their first game two years earlier. He’d outdueled Johnny Cueto, who would be traded to Kansas City later than season, and the two of them would help the Royals win their first World Series in thirty years.

Ventura was an unfinished product, taken way too soon. He made a name for himself as a fiery rookie in 2014, notably pitching seven shutout innings in Game 6 of the World Series to stave off elimination and force a Game 7. He pitched that game with RIP O.T. #18 written on his hat, a tribute to his friend and St. Louis Cardinals pitcher, Oscar Taveras, who had been killed in a car crash himself two days earlier.

Ventura’s 2015 season was a bit up and down, a young pitcher still finding his groove. He had a reputation for not backing down and stirring things up. I definitely remember one bench-clearing altercation with the White Sox on the South Side (not to mention a one-on-one bout with Manny Machado in Baltimore), and there was a lot of talk about him getting control over his emotions if he ever wanted to tap into the full depth of his potential.

My favorite memory of him from that season, outside of the game we saw him pitch, was him excitedly looking into a camera before storming the field after winning the ALCS. “We go to World Series again,” he laughed in his broken English. There was a little bit of cockiness in his expression, sure, but the joy that was also present really stresses how young he was.

2016 was more of the same, but he finished strong and there was a lot of hope that he would take a big step forward and become the true ace of the Royals staff in 2017. They already called him Ace anyway. (Ace Ventura, get it?) And then the news hit about a car wreck and it was over, just like that.

I didn’t shed any tears over Ventura’s death. Not to sound cold, but it wasn’t my first dance with death. In the span of just a few years in the mid-2000’s, I lost all four of my grandparents, my mom unexpectedly passed away, and I had a good friend die from a drug overdose. When you lose that many people you truly care about and who are in your everyday life, it sort of hardens you against more distant losses.

That’s not to say I wasn’t affected. I never personally met Yordano Ventura, but that doesn’t matter. We hold these athletes in high regard, when we aren’t bad-mouthing them during a slump, and the longer they’re with our team and the more they accomplish, the more they mean to us. We live and die right along their successes and failures, so to speak, and when one of them is taken from us in such a manner, it hurts. The KC and MLB community at-large came together for a tremendous outpouring of grief in the wake of Ventura’s death.

In a sense, it reminded me of my first brushes with death. Perhaps not coincidentally, baseball was involved in that as well. At least, that’s how I remember it.

The first person I ever remember knowing who died was my great-grandpa Ware. My memories of him are vague. I don’t recall much about him personally, except that he was likable enough. I used to go with my grandma to visit him in the nursing home. The place was depressing as hell. Not the kind of place you’d see on 60 Minutes necessarily, but the experiences definitely made me averse to the idea of nursing homes, a mindset that has continued to this day. It stunk like stale cigarettes— it was the 80’s, so every resident smoked— and the halls and rooms were filled with sickly-looking old people who acted like they’d already checked out. Perhaps I’m remembering it unfairly, but that’s the impression I was left with.

At the graveside service, the preacher read a passage from the Bible that had the word naked in it, causing me and my cousins to snicker with laughter as our parents silently scolded us with their eyes. Afterwards, we went back to our grandparents’ house for a big dinner with extended family. Our relatives from St. Louis were back for the funeral, and one of them, Gary, who didn’t visit that often, split off from the other adults to play football with us in the yard. I think he might have even tossed us some underhanded pitches. Sure, he was a Cardinals fan, but I think that won us all over. I was six years old.

My mom tucked me in that night, and I remember feeling a little guilty that I didn’t feel more upset. It wasn’t like I hadn’t known Grandpa Ware, although it would be a stretch to say we were ever close. Of course, it didn’t help that I had no real concept of death at that point. I asked my mom why he had to die. I don’t remember what she said exactly. Something along the lines of it will happen to everyone, so there was no point in worrying about it, but it didn’t really sink in.

My godfather died a few months later. He was only 31 years old. I sort of remember the visitation, which is about as many memories as I have of the man himself. He didn’t live near us, but I do recall him being around one time. I think it might have been a Christmas party, but I’m not really sure. All I remember for certain is that he gave me my first sip of beer. Being only five or six years old, I didn’t care for it much, but he seemed like a good guy. I never got to know him any better.

I’d like to say that I was more distraught at his passing, but the truth is it didn’t affect me much. His death was an abstract event that happened in my periphery, but didn’t really change a thing in my day-to-day life. Then, less than a year later, Dick Howser died.

Dick Howser was the manager of the 1985 World Champion Royals, but let me give you a little background on the man before we get to that. He was a high school friend of Burt Reynolds, and the two of them attended Florida State together. Reynolds played football and studied acting, while Howser's pursuits led him to the baseball diamond.

He was undersized, but he earned his way on to the Seminole baseball team and all the way to an eight-year career in the Majors with speed and defense. Howser played for the Kansas City A’s, Cleveland Indians, and New York Yankees, earning the Sporting News Rookie of the Year Award in 1961. He finished his career with a .248 BA, 16 HR, and 165 RBI.

After retiring, he spent ten years as the Yankees’ third base coach, before leaving to take the manager’s job at his alma mater. He left Florida State after only one year though, when the Yankees managerial position opened up in 1980. He had a history with the Yankees, considered himself part of their exclusive club, and had even managed them for a single game in 1978 in an interim role— it was too good of an opportunity to pass up. Interestingly, he got to see both sides of the intense Yankees-Royals rivalry in a way few others would.

Howser had a reputation for standing up to George Steinbrenner, the domineering Yankees owner. He had very little patience for the Boss’s nonsense, often refusing to answer the clubhouse telephone when Steinbrenner called. Generally seen as stricter than the more excitable Billy Martin, he was smart enough to pick his battles. For instance, he let Reggie Jackson slide on Steinbrenner’s no facial hair rule because he understood what really mattered and had no desire to hassle his star over something so trivial. He was also extraordinarily loyal, which spelled the end of his time in pinstripes.

Following Game 2 of the 1980 ALCS, Steinbrenner wanted 3B coach Mike Ferraro fired for sending Willie Randolph home to get thrown out on a play in the eighth inning. Howser refused, and after the Yankees lost the series, he was dismissed, despite winning 103 games that season.

The following season, Howser was hired by Kansas City to finish out the strike-shortened season. He got the Royals into the playoffs, but they lost to Oakland in the ALDS. After finishing second in the AL West in 1982 and 1983, he and the Royals broke through in 1984. It was supposed to be a rebuilding season, but Kansas City surprised everyone by winning the AL West, before losing to Detroit in the ALCS.

In 1985, the Royals started slow before putting it all together. They took a four-game series from the Angels in the next-to-last series of the season to put them over the top in the AL West, and then won in dramatic comeback fashion against Toronto in the ALCS and St. Louis in the World Series to capture the franchise’s first championship. The World Series victory came at the expense of Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog, who held the all-time wins mark by a Royals manager. Howser seemed destined to break that record, but it never happened.

The following July, the American League won the All-Star Game, 3-2. As manager of the defending AL champs, it was Howser’s honor to lead the AL club, but he admitted to having headaches and feeling sick beforehand, and even the announcers took notice of him messing up while trying to signal for a pitching change. Such mistakes were not commonplace for Dick Howser.

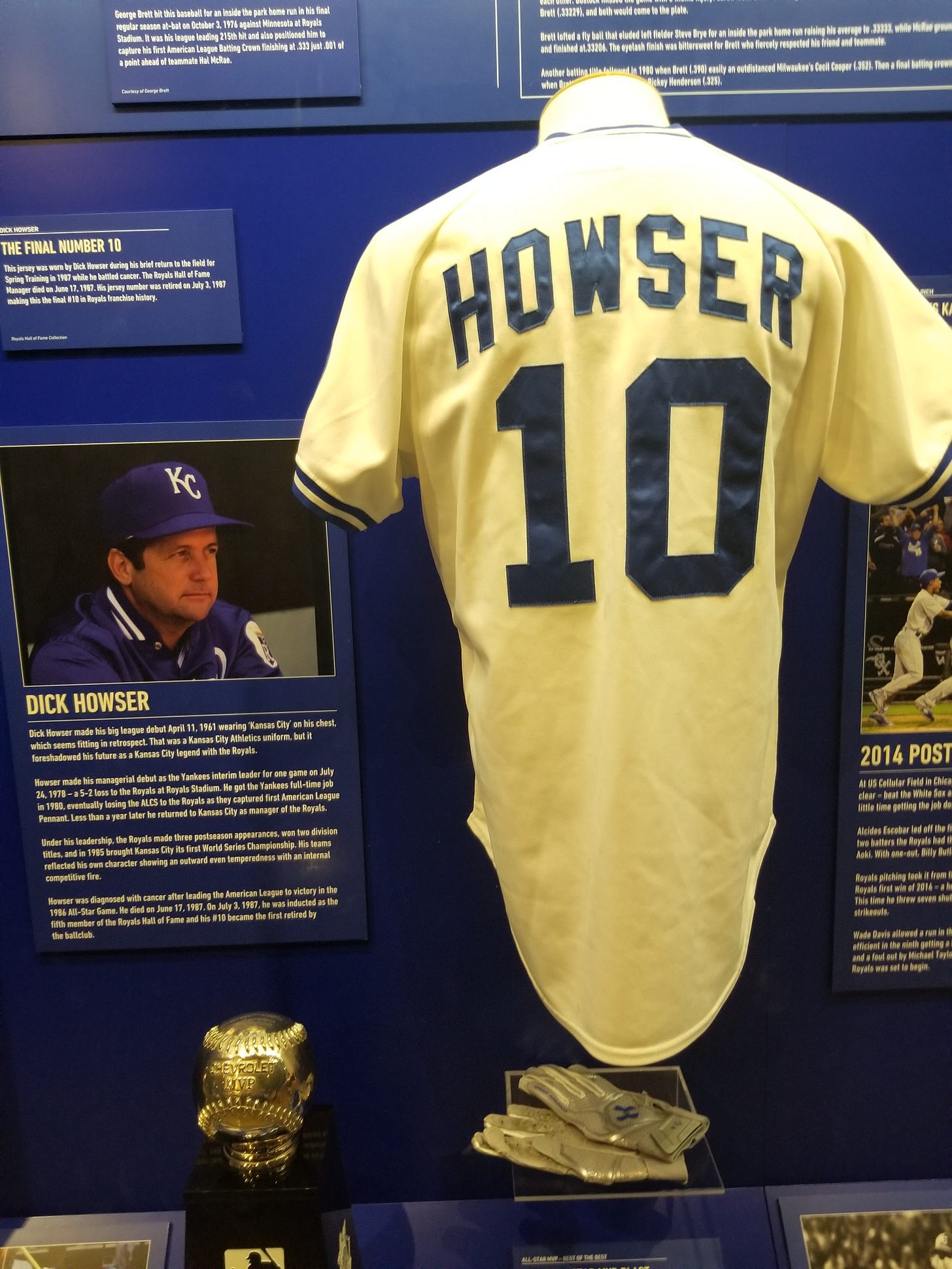

Two days later, Howser was diagnosed with a brain tumor. He underwent surgery and doctors found a malignant tumor in his left frontal lobe. After sitting out the remainder of the season, he attempted a comeback during Spring Training in 1987, but probably pushed himself too hard. Two days after reporting, a weak and exhausted Howser resigned for good and turned the team over to Billy Gordon.

He had another surgery that March, but it was unable to do the trick, and he died on June 17, 1987, just eight days after my eighth birthday. It cast a pall over that summer, and was perhaps the first time I realized that the Royals were not indestructible. I suppose their lackluster 1986 season should have clued me in, but I was only seven years old. Cut me some slack.

Howser was one of three Royals of that era to succumb to brain cancer— Dan Quisenberry and Ken Brett being the others. Add that to the number of Phillies players who’ve fallen prey to it after playing at Veterans Stadium, and I have a feeling that we’re not far away from a groundbreaking report on the unseen dangers of artificial turf, but I digress. The loss of Howser hit the Kansas City community and Royals fanbase particularly hard.

For one little kid, it was proof that not even Royals champions were safe from death. Suddenly, my mom’s attempts to comfort me took on a slightly darker tinge. She hadn’t meant it like that, but she was right. If Dick Howser could die, it could (and would) happen to all of us. That’s the moment I began to grasp the true inescapability of death.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not blaming Dick Howser for all the bad teenage poetry I wrote or the self-destructive choices I would later make, but it was a kind of landmark day for me. With the assistance of maturity, I’d like to point back to it as one of those moments that made me realize both that baseball is just a dumb game and that its greatness should also never be taken for granted. Everything, even baseball, is fleeting. But if I’m being honest, the only things I felt at the time were probably just a combination of fear, confusion, and sadness.

Those feelings never go away completely when you’re dealing with death, although I suppose experience does help take the edge off, just a little bit. So I guess I owe Dick Howser for that. Not only did he lead my team to its first championship, providing one of the greatest memories of my childhood, but his death helped prepare me for much worse losses to come. How much it actually helped is up for debate, but that’s not the point. His friends and family probably don’t take much comfort in that, but we tend to make things about ourselves, and I’m the one typing this out, so we’ll stick with this train of thought for the time being.

I have no doubt that there are many people who have missed Dick Howser far more than me, but his memory belongs to us all now. In 2009, the Royals renovated Kauffman Stadium and placed three statues around the structure. The first two are fairly obvious if you know your Royals history— George Brett and Frank White— but the third is Dick Howser. I don’t know if it is as popular of a destination for fans, given that Howser was a manager and not a player, but I always try to stop by when I’m at the K and pay my respects. It’s the least I can do for the man who made me painfully aware of my own mortality.

Fortunately, the Royals retired Howser’s number 10 two weeks before he died. I don’t know what kind of shape he was in at that point, but he was at least aware of the honor. Between that and the statue, his name and memory will live on as long as the Kansas City Royals exist.

Proof that even death has its limits.

Thanks for reading Powder Blue Nostalgia. Please feel free to share your Dick Howser memories in the comments below. Or tell us what baseball death affected you the most.

Thanks Patrick, I appreciate the info about Dick Howser and his impact on you with his death. I remember it hit me hard as well due to the highs of 1985, just didn't seem fair. It just makes you realize life is short, enjoy every moment you got! Until next time...

Poignant post, Patrick! Thanks for being so revealing about your personal losses as well as those on your favorite team. From an Astros POV, there have been early or unexpected passings, I'm sure, but I particularly remember the crushing blows to players' careers due to injury or other malady. Dickie Thon and J.R. Richard come to mind.

Although he was a Cardinal at the time, I took Darryl Kile's death pretty hard. It was sudden, but he was the first Astro I'd ever gotten an autograph from. As a kid, I never really bothered with that aspect, and while I collected cards in the '60s (that I now wish I still had!!), I re-kindled the hobby sometime in the late '80s when I was in L.A. I saw the Astros at Dodger Stadium sometime (I believe) in 1991 (I was 36 at the time), Kile's first season up. I had brought a whole stack of Upper Decks and Topps, and was poised with a Sharpie!

During warm-ups, I had situated myself in the first row, just behind the 'Stros' 1st base dugout, near the outfield-side dugout steps. Suddenly, I saw Kile walking straight toward me from where I guess he was throwing in the outfield bullpen. Strikingly handsome, he was smiling as I asked, "Hey, Darryl, can I have your autograph?" I'm sure a "please" must've been in there, somewhere! Impossibly charming was my take-away (that and his autograph)!

It was likely after this encounter (and watching kids fumble at the same exercise) that I devised a little tool to help make this endeavor more pleasing for all involved: I bought a small clipboard onto which I could secure a card under its "springed" clip. With this, I could hand the clipboard to the player, and he could sign without having to find a hard surface, he wouldn't bend it in his hand for security...it was just secure for all involved! Plus, I could just shove the roughly 4" x 6" clipboard into the back of my pants or shorts!

In several more years of collecting in the '90s (including by mail....there's a cool story!), I never saw my technique replicated or adopted by any other "hound"! Good stuff, Patrick! BTW, MLB just released their updated farm system rankings: Royals #29, 'Stros 30th! *sigh*