I debated what to title this post. Titles are one of my least favorite things about writing, and what is a title if not a fancy name? And let’s face it, names are quite often ridiculous.

So my first instinct of What’s In A Name? didn’t feel right at all. A Shakespeare reference was probably too classy for what I have in mind here. Then I remembered sitting in the backseat of the car with a friend when I was a kid, being chauffeured from one place to another by a parent with the oldies station on the radio, mindlessly rolling through numerous versions of the Name Game song like an out of tune CD player stuck on repeat. You know the song:

Shirley!

Shirley, Shirley Bo-ber-ley

Bo-na-na fanna Fo-fer-ley

Fee-fi-mo-mer-ley

Shirley!

That’s from the actual song by Shirley Ellis. I’m not sure I’ve ever actually known anyone named Shirley, but you get the idea. You start off with my name, then your name, then the next person’s name, and work yourself up to increasingly ridiculous names that are more and more difficult to smoothly incorporate into the song. If you’re anything like me and my friends, some baseball player names were going to be thrown in there, until the game finally collapses entirely into a fit of immature laughter.

That’s more the vibe I was going for. And no sport embraces the idea of absurd names better than baseball, whether they’re given at birth or thrown out by a teammate on a lark and manage to stick, for better or worse. Very little has changed since the time when I was a ten-year-old sifting through packs of baseball cards. Back then, if I found a name that struck me as funny, regardless of whether the card was worth anything, I’d set it aside to show my friends later. Now, as a forty-something, if I come across a dumb name while doing research on Baseball Reference, I’m still just as likely to screenshot it and text it to a friend.

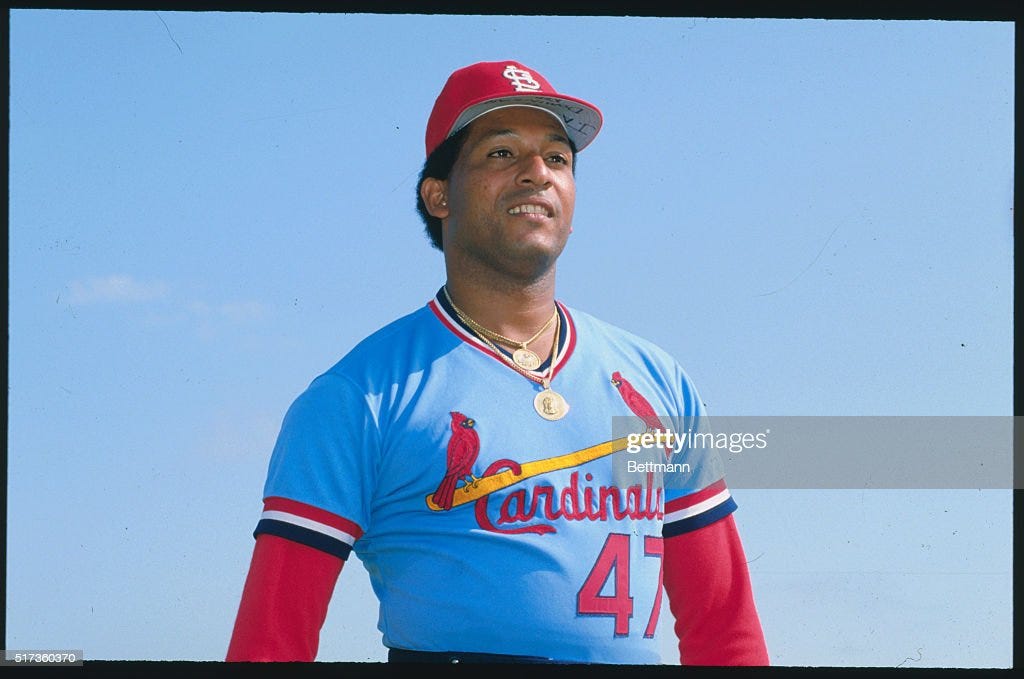

More often than not, these names tend to appeal to the more juvenile side of my sense of humor. Johnny Dickshot. Dick Pole. Chicken Wolf. You get the idea. This shouldn’t be too surprising. The first player name to ever really capture my attention as a kid was Joaquin Andujar, who pitched for the Cardinals against my Royals in the 1985 World Series. A perfectly normal name on the surface, but every kid I knew immediately transformed it into “Walking Underwear,” and that’s how I’ve thought of him ever since.

This was nothing compared to when we got a little older and our minds got a little dirtier. Every kid I knew lost their mind when they stumbled upon their first Rusty Kuntz card. (For the record, Kuntz is pronounced with a long u sound, but you try telling that to adolescent boys.) I don’t really remember Rusty as a player— he retired just as I was getting started as a baseball fan in 1985, though he would go on to become the likable first base coach for the Royals during their pennant runs in 2014-15— but his cards were always very popular.

If you’re wondering if such a reaction should be taken as an indictment of my generation in particular, allow me to assure you that this sort of thing stands the test of time. You should have seen my son when he first heard Albert Pujols’ name. There I was, trying to tell him all about arguably the greatest player of the twenty-first century, and all he could do was stand there, giggling like a simpleton, repeating “poo-holes” over and over in comic disbelief.

Baseball does weird things to your brain.

Plenty of lists compiling funny names exist to support that statement. Most of them are pretty meh. The best I’ve seen is probably the newsletter, Dead Legends, which highlights a different name in every issue, along with a quick backstory.

The last thing I want is to step on their toes, but I do want to highlight some of the more memorable baseball names from my youth. Some are given names, others are nicknames, and I won’t pretend that any of them are laugh-out-loud hilarious. Most humorous baseball names aren’t, unless you really want to lean into your inner eight-year-old and focus on the Rusty Kuntz’s of the world. But they are memorable.

Memorable in the same way that Rollie Fingers was memorable. Well, actually, that’s probably not quite accurate. None of the players I’m going to mention were half as good as Fingers, who also happened to sport maybe the greatest mustache in the history of the world. But if his name wasn’t Rollie (short for Roland) Fingers, would he be remembered as just another Hall of Fame pitcher, instead of the singular baseball character he is? Again, probably not. With that mustache, he was always going to stand out. Perhaps Fingers is a bad example, but I couldn’t not mention him.

Take Goose Gossage instead. Another Hall-of-Famer with an impressive handlebar mustache of his own, Rich Gossage supposedly earned his nickname from a teammate for the way he stretched his neck out like a goose when he was reading the signs from the catcher. Or maybe a friend hated everyone calling him “Goss” and tweaked it to “Goose.” Depends on who you ask. And he was undoubtedly a great pitcher, but you can’t tell me his distinctive nickname hasn’t helped him stand out from the pack. I’m not saying it’s the only reason he’s in the Hall of Fame and Dan Quisenberry isn’t, but it’s a theory.

The same goes for Catfish Hunter, who was given his nickname by A’s owner Charlie Finley. Finley determined that his talented young pitcher needed a catchy nickname, and he called him Catfish— probably because Hunter liked fishing, though with Finley it’s hard to say for certain. Hunter was a Hall-of-Fame pitcher too, so I’m not trying to take anything away from him, but there’s a reason he’s still as popular as he is, and it’s got nothing to do with his fastball.

Or consider Kennesaw Mountain Landis, the first commissioner of baseball. Named after a Civil War battle in which his father was wounded, Landis, a respected judge, was brought in to clean up the game after the 1919 Black Sox scandal. He accomplished that, though he also reinforced the color barrier that would keep the game segregated until Jackie Robinson came along. So, let’s just say his legacy is mixed, at best. But while even most hardcore baseball fans struggle to name past commissioners, especially those who predate them, Landis is still relatively well-known. A big part of that is his distinctive name.

So, without further ado, here are some of the most memorable baseball names from my childhood.

I’m not a big Chris Berman fan. His whole schtick of giving players ridiculous nicknames while he presented highlights on ESPN was funny at first, but I felt it grew tired pretty quickly. I’m not the only one who felt that way either. In the mid-80’s, ESPN told him to knock it off. So imagine my disappointment when I later learned that my boyhood idol, George Brett, who was apparently a big fan of the bit, made a stink about it and forced ESPN to back off. It’s always the ones we love that hurt us the most.

Berman’s nickname for McDowell was Oddibe “Young Again” McDowell, which isn’t terrible as far as Berman nicknames go, but always felt completely unnecessary to me. I mean, the guy’s name is Oddibe. How many Oddibe’s have you ever met? Just roll with that.

It’s a fun name to say. Let it bounce around in your head a little. If you want to say it out loud, stretching it out as you flap your finger across your lips, I won’t judge you. We used to do the same thing when we were kids.

Oddibe led off the first game I ever saw in person, when the Royals hosted the Rangers in 1985. I’ve written about this before, but I was convinced for many years that he led off the game with a home run. Only recently, after finding the box score, did I realize that never happened. He still had a fine game, going 3-4 with a run and a stolen base, and he certainly made an impression on me, even if it wasn’t entirely accurate.

That game, and especially my misperception of it, is not a bad characterization of McDowell’s entire career. His potential was through the roof. He won the Golden Spikes Award (College Baseball’s Best Player) at Arizona State, and was later inducted into the College Baseball Hall of Fame. Drafted twelfth overall by the Rangers, he finished fourth in the Rookie of the Year voting in 1985. Roughly a month before I first saw him in action, he became the first Ranger ever to hit for the cycle in an 8-4 win over Cleveland.

And yet, that was probably the peak of his major league career. It would be unfair to label him a bust, but he just never materialized into a star player. At best, he was a poor man’s Willie Wilson or Willie McGee— a serviceable leadoff man with great speed and an okay bat, destined to become a journeyman. His career numbers were:

.253/.323/.395, 74 HR, 266 RBI, 715 H, 458 R, 125 Doubles, 28 Triples, 169 SB, .718 OPS, 95 OPS+, 10.6 WAR

And, in a weird addendum to his story, which feels like it could only happen to a guy named Oddibe, he was also the subject of a recurring piece in Deadspin, when they mistakenly gained access to his water bill from Broward County, Florida for over a year in 2011-12. It was a tongue-in-cheek bit that mostly consisted of the website listing his water usage and fees, but it proved quite popular. There’s even an oral history of it, compiled after Broward County Waste & Wastewater Services finally blocked their access.

I doubt it would have caught on if they’d been posting former major leaguer Bill Jones’ water bill. But when your name is Oddibe, people are going to pay attention.

Buddy Biancalana was a fairly forgettable shortstop, but two things endeared him to me. First, he played for the 1985 Kansas City Royals. To be fair, that’s usually enough to win me over on its own. And even though he only started 35 games for the Royals that season, Dick Howser went to him down the stretch, benching Onix Concepcion in late September and riding Biancalana throughout the postseason. And Buddy delivered, posting a .435 OBP with 2 R and 2 RBIs in the World Series, despite never being much of an offensive force.

His career numbers: .205/.261./.293, 6 HR, 30 RBI, 113 H, 70 R, 8 SB, .553 OPS, 51 OPS+, -1.6 WAR

The second thing I liked about him was that his name was fun to say. Biancalana just rolls off the tongue in a pleasing way, practically begging you to throw in an over the top Italian accent as you say it. There’s nothing inherently funny about the name itself, but it still manages to bring a smile to my face.

David Letterman agreed with me. Never one to shy away from a word he found amusing to say, Biancalana became his favorite baseball player in 1985. He even introduced the Buddy Biancalana Hit Counter that season as a way to parody the hype over Pete’s Rose’s pursuit of Ty Cobb’s all-time hit record. Rose did eventually pass Cobb that season, but I think Letterman really just wanted an excuse to work Biancalana into every episode.

Buddy was cool with the joke, and even went on the show to present Letterman with a bat after the Royals won the World Series. I wish I could say I was watching when it happened, but I was six at the time, and Letterman was on way after my bedtime. However, discovering this episode years later only made me more appreciative of one of the more overlooked ’85 Royals.

Dickie Thon was probably my favorite baseball name when I was a little kid. Finding one of his cards in a pack never failed to illicit a laugh, for obvious reasons. Again, keep in mind that I was just a little kid. Although, that said, I still find the idea of a grown man going by the name of Dickie fairly ridiculous.

So it doesn’t seem fair that Thon’s career played out in almost tragic fashion. Well, tragic is perhaps a bit overdramatic. But it could have been so much better.

Dickie Thon’s career took off when the Angels traded him to Houston in 1981. He quickly won the shortstop job and put together back-to-back standout seasons in 1982 and 1983.

1982: .276/.327/.397, 3 HR, 36 RBI, 73 R, 31 Doubles, 10 Triples (led NL), 37 SB, .724 OPS, 110 OPS+

1983: .286/.341/.457, 20 HR, 79 RBI, 81 R, 28 Doubles, 9 Triples, 34 SB, .798 OPS, 127 OPS+

Bill James wrote that Thon appeared to be on pace for a Hall-of-Fame career, but by the time I came around, that trajectory had been altered significantly.

Early in the 1984 season, Thon was hit in the face by a pitch, breaking his orbital bone and permanently affecting his perception. He was never the same player after that, effectively becoming an average middle infielder and journeyman with a funny name, which is how I remember him.

Ironically, he and Biancalana were teammates in Houston in 1987, but the Dickie-Biancalana double play combo never saw much play, since both spent most of the season on the disabled list. Biancalana probably came out the better for it. Even after the eye injury, Thon was by far the superior player. His career statline:

.264/.317/.374, 71 HR, 435 RBI, 1,176 H, 496 R, 193 Doubles, 42 Triples, 167 SB, .691 OPS, 95 OPS+, 23.9 WAR

No one is going to be pushing him for the Hall of Fame with those numbers, which is a shame (because in a museum that features Cum Posey, he wouldn’t even have the most snicker-inducing name), but Dickie Thon still had a solid career.

It got really difficult toward the end, but I made it through this whole section without making a single blatant dick joke. Please congratulate me.

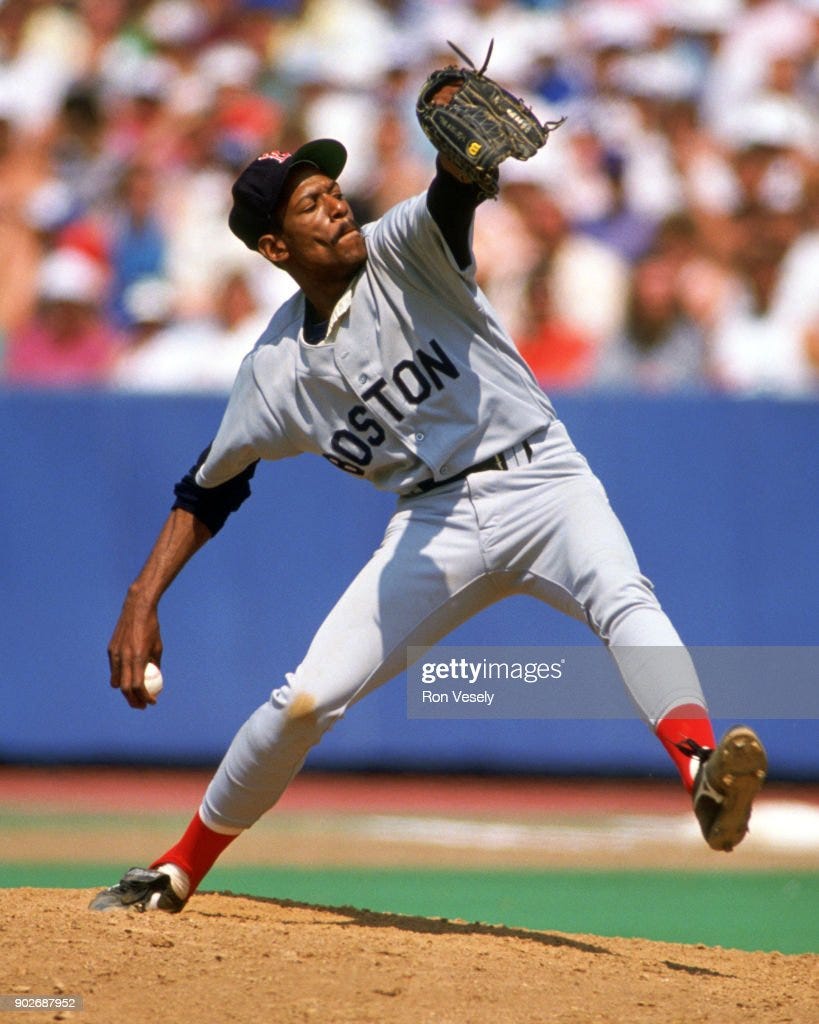

Like many of the subjects featured in this article, Dennis “Oil Can” Boyd can be described as a player who had the potential to be truly great, but never really reached that level for a variety of reasons. The chief reason with Boyd was drugs and alcohol.

As a kid, I always attributed his nickname to his pitching mechanics. Boyd was extremely lanky and he pitched with all sorts of exaggerated movements. I thought they called him Oil Can as a joke, because his body needed regular tune-ups to keep it functioning on the mound. This was not the case.

The common story around baseball was that everyone called him Oil Can because of his Mississippi roots. Beer was referred to as “oil” in Mississippi, or so they said, and it was well-known that Boyd enjoyed a drink. But he disputed that. Boyd said he got the name as a kid when he and a friend were caught drinking whiskey out of oil cans.

I have no reason to doubt him. None of it sounds out of character. This is a guy who has admitted to smoking crack every day of the 1986 season and often pitched with a few rocks stashed under his cap. So yeah, I have no problem believing the story.

The crazy thing is that 1986 was his best season. He went 16-10 with a 3.78 ERA, 214 IP, 129 K, and a 1.246 WHIP. This came on the heels of a similarly strong 1985 season. Of course, in typical “Oil Can” fashion, nothing about that season could be that simple.

In addition to his rampant drug abuse, Boyd was one of the most emotional players in all of baseball. This could sometimes work for him. Without a doubt, it helped power him through his best performances on the mound. But more often than not, it worked against him. And while I’m no psychologist, I have to believe it played a role in his need to self-medicate.

That wasn’t the only way it exhibited itself though. Given to wild mood swings, he briefly quit the Red Sox during their magical 1986 season after being snubbed for the All-Star Game. Fortunately, he was quickly convinced to come back, but it’s clear he never really felt at home inside the Boston clubhouse.

He claimed that Red Sox 3B Wade Boggs frequently directed racial slurs at him and other black teammates, an accusation that I’m in no position to confirm or deny. But either way, regardless of who was in the right or wrong, it was evidence that the locker room chemistry was far from ideal.

Boyd got sideways again with the Red Sox during the 1986 World Series. He was scheduled to start Game 7, coming on the heels of the Buckner error and Red Sox collapse in Game 6, but was bumped in favor of Bruce Hurst after the game was rained out and pushed back a day.

“Oil Can” had every reason to be disappointed and upset, but Red Sox manager John McNamara was hardly out of line to make the move. Not only was Hurst their best pitcher after Roger Clemens, on pace for a potential World Series MVP if Boston pulled it out, but Boyd had struggled mightily in Game 3. The Mets thought he was easy to rattle, and some, like Lenny Dykstra, allegedly had no problem using racial slurs to get under his skin. Given a choice, they would have preferred to face Boyd instead of Hurst.

Boyd didn’t see it that way, and instead of bowing to his manager’s decision and preparing to help his team in any other way he could, he supposedly showed up drunk and unable to play in Game 7. He disputes the accusation, but the story illustrates why he never reached his true ceiling. Like just about everyone featured in this article, he went on to have a decent, but otherwise unremarkable career, posting a final statline of:

78-77, 4.04 ERA, 1,389.2 IP, 799 K, 1.292 WHIP, 17.3 WAR

If not for his nickname, he might not be remembered at all.

Luckily, for those of us who remember Boyd’s talent, we may be getting a second chance to see it realized, albeit indirectly. Current Cleveland Guardians pitcher Tristan McKenzie bears a remarkable resemblance to “Oil Can” in both his physique and mechanics. Though still early in his career, McKenzie has shown flashes of Boyd’s upside without his predecessor’s demons. Here’s hoping that continues to be the case and he reaches his full potential, unlike the other players I’ve featured today.

Because there’s more than one way to make a name for yourself in baseball.

Thanks for reading Powder Blue Nostalgia. Got any baseball names that make you giggle? Leave ‘em in the comments!

Nathan Adcock. Chien-Ming Wang. Tim Belcher. Jerry Cram. Brooks Pounders. And those are just some mediocre Royals pitchers.

Tristain Mckenzie is also a low key fun name as well (probably because I have not seen to many baseball players with the name Tristian) (and yes i know i spelled his name wrong)