Not long after Dayton Moore took over as General Manager of the Kansas City Royals in 2006, he was asked about his philosophy and his plans to turn around arguably the most moribund franchise in Major League Baseball. He said a lot of things, but perhaps his most telling comment was “pitching is the currency of baseball.” Starting pitching, in particular.

Moore, in my opinion, had one of the most unique GM tenures in baseball history. It lasted fifteen years, which is an unusually long time on the job for any GM in professional sports, even a very successful one. But Moore was not overwhelmingly successful. The Royals only posted three winning seasons in his time in Kansas City. That’s like batting .200, and .200 hitters don’t tend to stick around for a decade-and-a-half.

Sure, he took over a franchise that was a total disaster. Even when the rebuild wasn’t moving along as quickly as planned, that bought him some extra time. And going to back-to-back World Series in 2014-15 certainly earned him a grace period as well. However, when the core of that team departed, his attempts to rebuild it again did not go so well and he was fired late in the 2022 season. The Royals are now back in a spot that feels eerily similar to when Moore took over. Maybe not quite as bad overall, but they’ve had three 100-loss seasons in the last six years, so things haven’t been great.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of Moore’s failure in Kansas City is that he never figured out the starting pitching side of things. He knew how important it is to sustained success, and he actually succeeded in finding ways to supplement it and work around its weaknesses — he revolutionized bullpen usage during the Royals’ championship runs — but he never unlocked the secret of building a solid rotation.

It wasn’t for lack of trying. See his 2018 draft, in which he used his first five picks on college pitchers, or taking Frank Mozzicato with the seventh overall pick in the 2021 draft. The book isn’t closed on any of those guys yet, but the results so far have been less than promising. And very few of his other moves, outside the charmed period of 2013-15 (looking at you Jeremy Guthrie and Edinson Volquez), have panned out much better.

He’s caught some tough breaks along the way. The tragic death of Yordano Ventura was something that no one could have seen coming, and Danny Duffy showed a lot of promise, but never stayed healthy enough to take his game to the next level. He also brought a lot of heat down on himself with unforced errors. Yes, Royals fans, I’m referring to his stubborn insistence on retaining Cal Eldred as the pitching coach.

The thing is, if anyone out there should know what a great pitching staff looks like, it’s Dayton Moore. He began his career as a scout with the Braves in 1994 and worked his way up through their organization before landing his gig with the Royals. As such, he had a front row seat to the greatest pitching rotation of my lifetime. Maybe ever.

That’s who I want to focus on today. There have been several attempts to top it in my lifetime — the 2011 Phillies and 2019 Astros come to mind — and many solid candidates who predated them — look at the Orioles and A’s in the 70’s, well before I came along, and the Mets of the mid-to-late 80’s, who I did actually get to watch — but the 90’s Braves remain the best I’ve ever seen.

Right about now, several readers are aching to point out that the Braves only won a single championship with that staff. This is true, but I don’t care, so save it. Yes, they didn’t cash in as much as they should have. No denying that. We probably place too much emphasis on rings though. That’s not an excuse. Championships are the highest goal and that should be what every team strives for. But my point is that winning championships is hard. Let’s not allow a lack of flags flying over old Turner Field to overshadow the brilliance of the players who regularly dominated from its mound.

And they did dominate, make no mistake about it. In addition to their one World Series title in 1995, the Braves won fourteen straight division titles from 1991-2005. (Out of respect to the Expos, I’ll point out that Montreal was leading the NL East in 1994 before the season was prematurely ended by the Strike. Who knows how that would have played out?) They might have only taken home the crown once, but they made five World Series appearances in that time span. They had an outstanding lineup, but a lion’s share of the credit belongs to their starting pitching rotation.

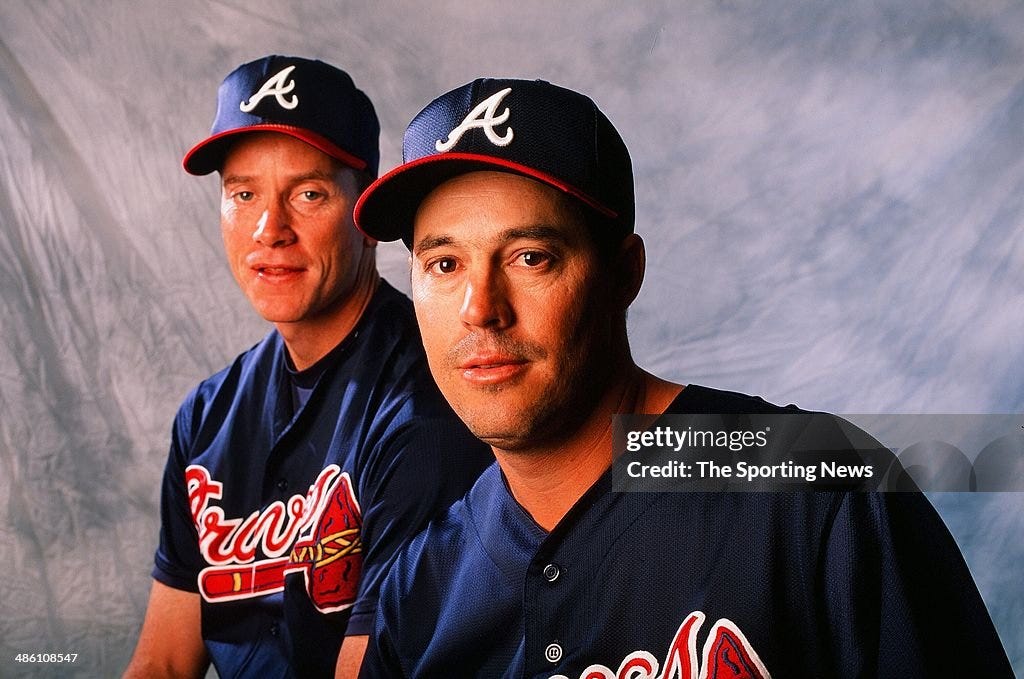

Four players formed its core: Greg Maddux, Tom Glavine, John Smoltz, and to a lesser degree, Steve Avery. The fifth spot rotated on a yearly basis, more or less, but it was never manned by a slouch. And Avery didn’t have the longevity of the others, opening up another spot for more contributors as the decade went along. Kent Mercker, Kevin Millwood, and Denny Neagle are just a few of the backend guys who stood out to me for the Braves. The Big Three, however, were on another level entirely.

I’m not going to dive deep into their stats or try to give you a complete rundown of their many accomplishments. This thing will go twenty pages if I do that, and there are plenty of other resources to get that information. Start with Wikipedia and YouTube and work your way out. But I can’t write a newsletter about baseball in my youth without providing some kind of tribute to the 90’s Braves staff, so here are a few of my personal impressions of each. I’ll try to make it quick and to the point.

Greg Maddux

Career stats: 355-227, 3.16 ERA, 5,008.1 IP, 3,371 K, 1.143 WHIP, 106.6 WAR

Quite simply the best pitcher I’ve ever seen. (Peak Pedro Martinez might be number two.) Did he benefit from an expanded strike zone provided by favorably disposed umps? Absolutely, but he earned that over a career of dominant pitching.

He’s the only player in MLB history to record 300+ wins, 3,000+ strikeouts, and less than 1,000 walks. He threw a 78-pitch complete game in 1997, one of 31 career games in which he threw less than 100 pitches in nine innings of work. Major League pitchers today would kill for that kind of efficiency.

But none of that is why I loved Maddux so much. I loved him because he was a dork. I first started rooting for him when he was with the Cubs because he wore glasses. I wore glasses, and believe it or not, I was a dork too. To see the way he pitched, with intense competitiveness mixed with joy (Maddux was an infamous clubhouse prankster), it gave me hope that baseball didn’t have to be dominated by jocks and that someday maybe I could pitch like him.

Of course, I never did, but hope, no matter how far-fetched, is invaluable to a kid.

Tom Glavine

Career stats: 305-203, 3.54 ERA, 4,413.1 IP, 2,607 K, 1.314 WHIP, 80.7 WAR

Glavine was more of a prototypical pitcher than Maddux, but to me he will always be one of the quintessential Braves of the era. Unlike Maddux, who didn’t join the Braves via free agency until 1993, after Atlanta had made their first two World Series appearances, Glavine was there from the start.

He debuted with the team in 1987, while the Braves were still mired deep in their doormat phase, which lasted most of the 80’s. He struggled a fair amount in the beginning as well, but his gradual improvement over the next three years mirrored that of the organization’s at-large. In 1991, it finally clicked for both Glavine and the Braves, and they made the remarkable climb from worst team in the division to the World Series.

Glavine is perhaps the most overlooked of the Big Three. His numbers aren’t as gaudy as Maddux’s, and his career didn’t have the wild twists and turns that John Smoltz’s did, but he was a picture of steady excellence for over a decade in Atlanta.

John Smoltz

Career stats: 213-155, 3.33 ERA, 3,473 IP, 3,084 K, 154 saves, 1.176 WHIP, 69.0 WAR

Speaking of Smoltz, he is probably best known today as a polarizing announcer on Fox’s MLB coverage. Listening to him bemoan the current state of the game, it’s not uncommon for listeners to wonder if he even likes baseball. It’s a fair question, but don’t let that fool you into underestimating the ability he had on the mound.

Smoltz had more speed and power than either Maddux or Glavine, but he was not a limited pitcher in any way. He had a full repertoire of pitches to call on, which served him well through three distinct phases of his career. Smoltz began as a dominant starter for the Braves in the 90’s, but then he missed two years at the turn of the century due to Tommy John surgery.

Tommy John was not yet the routine procedure it’s become now, though great strides had been made by that time, and when he returned in 2001, it was as a closer in the bullpen. No less dominant in the ninth inning than he’d been in the first, Smoltz is one of only two pitchers in MLB history to record both a 20-win season and a 50-save season. (The other is Dennis Eckersley.)

But what’s even more amazing is that after four years of closing, he transitioned back into a productive starter again for the rest of his career. He holds the Braves’ records for most games pitched and strikeouts, and he put together an impressive 15-4 postseason record in 41 playoff appearances.

So, question his broadcasting ability all you want, but he took a back seat to no one on the mound.

Steve Avery

Career stats: 96-83, 4.19 ERA, 1,554.2 IP, 980 K, 1.349 WHIP 13.8 WAR

Finally, we come to Steve Avery, the what-if of the group. Avery came into the league with a lot of hype — I remember his rookie cards being sought-after commodities — but it just didn’t work out for him the way it did with the other three.

It looked like it might early on. His 1991 season was fantastic, and even if his win-loss numbers weren’t as good the following season (he suffered from terrible run support), his other numbers showed he hadn’t dropped off at all. He won the 1991 NLCS MVP with 16.2 innings of shutout ball, and he was still at the top of his game through most of 1993.

Then the wheels came off. Late that season, he suffered an arm injury and was never the same again. Some blamed the injury on overuse, but who knows? Whatever the cause, it makes Avery more relatable to modern pitchers. His career stats fell well short of traditional HOF pitching milestones, but they’re more than respectable. Combined with his short shelf-life, you could make that argument that Avery was simply ahead of his time. If he were pitching today, he’d probably be lauded in the same way as often-injured superstars Jacob DeGrom and Shohei Ohtani.

Back in the 90’s, however, he turned out to be a cautionary tale.

Thank you for reading Powder Blue Nostalgia. I hope you’re enjoying the offseason and the Hot Stove is cooking for your favorite team. If you’re a Royals fan like me, I invite you to check out my work on the Royals, past and present, at Kings of Kauffman, including this piece on the Seth Lugo acquisition and a look back at an iconic Willie Wilson walk-off inside-the-park home run that should appeal to all PBN readers. And don’t forget to share your thoughts on the 90’s Braves pitching staff in the comments below. Or, if you have a candidate for a better rotation, this is the place to make your case. Just remember it’s only an opinion, so let’s not get too worked up over it. The holiday season is upon us, and no matter how you celebrate, I wish you all the best, even if your pick for the best pitching staff in baseball history obviously pales in comparison to the Braves.