Sports records are strange. We tend to revere them, but the truth is that we should take them all with a grain of salt. They’re generally next to worthless without context, and very few of them age well.

Don’t believe me?

Pick a sport and have a discussion with your grandpa about the G.O.A.T. Then have the same discussion with your kid. See how much you agree on.

Seriously, how are you supposed to fairly compare Wilt Chamberlain and Michael Jordan? They were incredibly different physical beings who played completely different positions with completely different strengths and weaknesses.

About the only thing they had in common is that they both played a game called basketball— though the game itself was radically different in their respective eras— and they were way better than everyone else they played against. But determining which was one was actually better is a futile exercise.

The same is true for football. John Elway was the best quarterback I’d ever seen when I was a kid. If he were playing today, I have no doubt he’d be doing Patrick Mahomes-type stuff and putting up similar numbers. But he’s not playing today.

He played two to three decades earlier, when offenses were more conservative and the rules favored the defense a lot more. As a result, many of his and his peers’ accomplishments have been erased from the NFL record book.

Does this mean they weren’t as good as we thought? Of course not. But it does shine a light on how unreliable the record books can be.

Baseball, in this respect, is somewhat unique. Among the major American sports, it has probably changed the least in the last century. (Not always a good thing, by the way.) Sure, the players have gotten bigger and faster, and certain aspects of the game like bunts and stolen bases (unfortunately, in the latter case) fall in and out of fashion, but the game would still be easily recognizable to a fan from a century ago.

Not sure you could say the same for fans of football or basketball. After all, they were using leather helmets and peach baskets back then.

This goes a long way toward explaining why baseball fans have long viewed the sport’s record book as only slightly less hallowed than the Bible. Even with all the improvement in athleticism and strategy, statlines separated by decades tend to have a remarkably similar feel to them.

Records fall, but they do so gradually, and entire generations of athletes aren’t written out of the book in a manner of ten years. Babe Ruth’s single season home run record lasted from 1927 to 1961, when Roger Maris topped it by one. Maris’s record lasted until 1998, when Mark McGwire bested it by nine with the assistance of performance enhancing drugs.

The steroid scandal gave the MLB record book a body blow it may never fully recover from. Now, I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again— 1998 was a lot of fun. Aside from its role in reinvigorating baseball after the 1994 Strike, it was just a hell of a ride.

Either out of ignorance or denial, we all looked the other way and simply enjoyed the show. The scandal didn’t come until later. When Barry Bonds hit 73 home runs three years after McGwire, the thrill was gone and no one could ignore what was happening anymore.

In 2006, Bonds hit his 756th career home run, breaking Hank Aaron’s career home run record in a cloud of controversy. These were some of the most cherished records in all of sports. For them to be broken in such a manner did irreparable damage to the record book.

Need proof of this? See the toxic discussion around Aaron Judge’s 62 HR season in 2022. The conversation quickly became about who is the real single season home run leader— Judge eclipsed Maris’ still-standing American League HR record and presumably did it clean, as opposed to McGwire and later Bonds.

The question is ridiculous, of course. Judge’s 2022 season was phenomenal. Assuming he isn’t busted for using some designer steroid in the near future, it will go down as one of the greatest offensive seasons in MLB history.

But as much as the PED scandal might rub us the wrong way, nothing that McGwire or Bonds did in the late 90’s and early 2000’s was technically against the rules. Yeah, it leaves a bad taste in our mouths and isn’t how we’d prefer it, but like it or not, Barry Bonds is the home run king.

Yet there is one record that still holds a special place in the hearts of baseball fans and isn’t likely to be broken any time soon. In 1941, Joe DiMaggio recorded a hit in 56 consecutive games. Steroids might help a player hit the ball farther, but they don’t help him make contact, and his record has never been in serious jeopardy over the last 81 years.

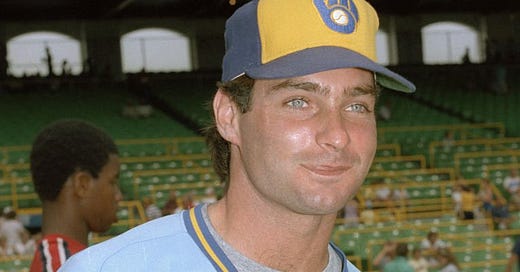

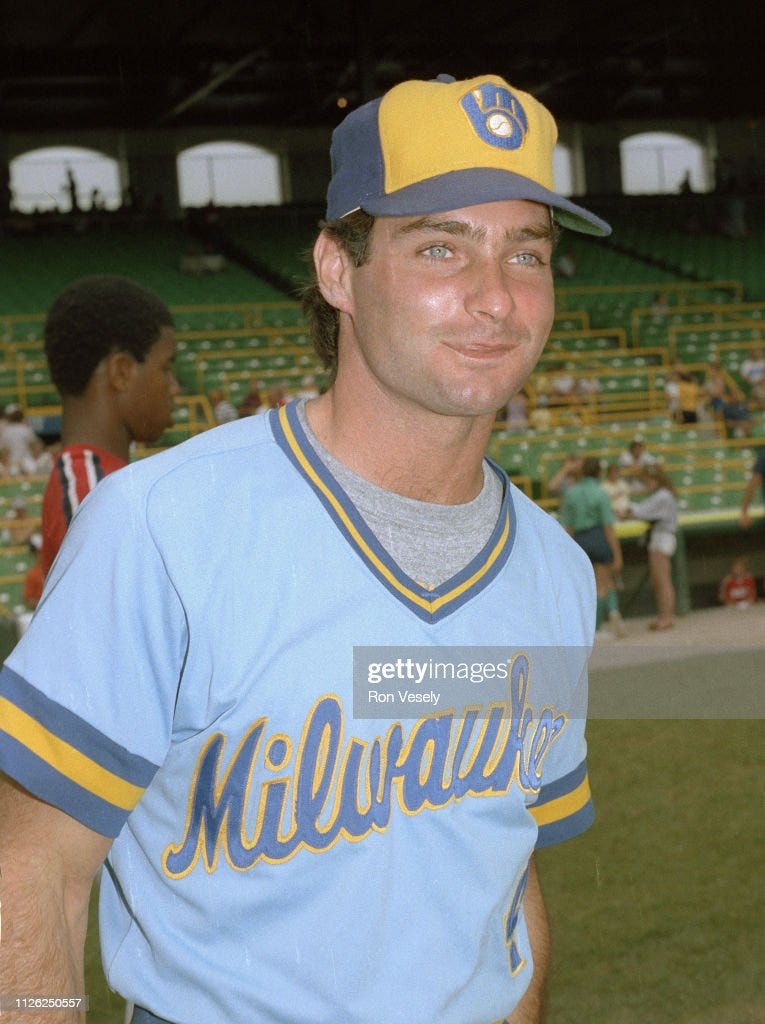

However, in 1987, Paul Molitor made a run at it. His streak fell well short at 39 games, which, in truth, is only good enough for sixth place on the all-time consecutive game hit list. On the surface, that doesn’t seem like a very big deal. But that’s not how it felt in 1987.

The streak reached 30 games on August 15, 1987. I know this because I was at Royals Stadium that night, watching the Royals lose to the Detroit Tigers 8-4. To be perfectly honest, I remember very few details about that particular game.

Checking the box score on Baseball Reference reveals that it was a Doyle Alexander vs. Danny Jackson matchup on the mound. Frank White and Lou Whitaker hit doubles, and both Alan Trammell and Lonnie Smith went yard. George Brett went 1-3 with an RBI and a walk. None of that made a lasting impression on me.

But I do remember them announcing that Paul Molitor had extended his hit streak to 30 games in a 2-1 loss to Baltimore that evening. Okay, I didn’t remember the part about the Brewers losing to the Orioles, but I definitely remember the hit streak announcement.

They put it up on the Crown Vision scoreboard, which was not nearly as advanced as it is now. The graphics looked like a cross between an Atari and the primitive computer we used to play Number Munchers on in school. But I can still see it flashing across the screen in pixelated letters, interrupting a completely unrelated game.

No one minded. Molitor’s pursuit had everyone’s attention. He was doing interviews on national TV shows that had no ties to baseball, and, of course, he was featured prominently on sports programming, reaching as far as coverage on ABC’s iconic Wide World of Sports. Had the streak extended into the forties, NBC was preparing to cut into other programming for each Molitor at-bat, similar to ESPN’s recent coverage of Judge’s HR pursuit.

Molitor was a great player, though far from the flashiest. I’ve never met anyone who has said that Molitor was their favorite player. He strikes me as the type of guy who is your favorite player’s favorite player, because he did everything so well, often under the radar.

He played for twenty years, which included hugely successful stints with the Milwaukee Brewers (1978-92), Toronto Blue Jays (1993-95), and Minnesota Twins (1996-98). An argument could be made that he was often the best player on his team, though he was usually overshadowed by teammates like Robin Yount (another Hall of Famer) and a slew of big names on a loaded Blue Jays roster.

One of the best examples of this is the 1993 World Series. The Blue Jays won the title over the Phillies in six games, and Molitor was named the MVP. He was phenomenal in that series, batting .500 with 2 doubles, 2 triples, 2 HR, and 7 RBI. Yet all anyone ever talks about when the ‘93 World Series comes up is Joe Carter’s epic walk-off HR to win Game 6.

Doesn’t seem fair for a guy whose career statline looks like this:

.306/.369/.448, 234 HR, 1,307 RBI, 3,319 H, 504 SB, .817 OPS, 122 OPS+, 75.6 WAR

He’s one of three players all-time with 3,000+ Hits, 600+ Doubles, and 500+ Stolen Bases. The other two are Honus Wagner and Ty Cobb. So yeah, pretty select company.

In Game 1 of the 1982 World Series, he became the first player to record 5 hits in a World Series game. Albert Pujols matched him in 2011. He hit .355 for the Brewers throughout the seven-game series, coming up just short of the Cardinals for the trophy.

He was also the first player to hit a triple for his 3,000th hit. Ichiro Suzuki joined him in 2016. In 1994, he stole 20 bases without getting caught, one short of Kevin McReynolds’ then-record of 21. Carlos Beltran currently holds the record with 24 in 2004. And Molitor is also the last player to steal home at least ten times during his career.

He really could do a bit of everything. A seven-time All-Star, one of his most impressive feats might have actually come off the diamond. Struggling with injuries early in his career, he started using cocaine and it quickly got out of hand. Given an ultimatum by his wife, he went to rehab and successfully cleaned up, though he later suffered the embarrassment of being named in one of the numerous drug trials that swept through Major League Baseball in the early 80’s.

This was never on my radar though. He always struck me as a bit of a clean-cut guy, and I didn’t discover this chapter of the Paul Molitor story until I began researching this story. Even when it came to drug infamy, the guy was overshadowed by more household names like Keith Hernandez and Willie Wilson.

The one exception to this was his pursuit of DiMaggio in 1987. From July 16th to August 25th, the spotlight was rightfully on Paul Molitor. And if you look at the highlights of the streak itself, it provides a fairly indicative sample of what made Molitor such a fantastic ballplayer.

On August 9th, he doubled in the top of the ninth vs. the White Sox, helping the Brewers add several insurance runs to cap off an 8-4 victory.

He homered in the ninth against Baltimore four days later, though the Brewers still came up a run short.

Molitor showed off his speed on August 17th, beating out a bunt to extend the streak to 32 games.

Two days later, he had arguably his single best game of the streak against Cleveland, ending up only a triple shy of the cycle. This was after starting the game with back to back groundouts and singling twice.

Perhaps most importantly, the Brewers reeled off a thirteen game win streak in the midst of Molitor’s run. There’s no doubt that he made every team he was on better. Here are his final 1987 stats:

.353/.438/.566, 16 HR, 75 RBI, 114 R (led the AL), 41 Doubles (led the AL), 5 Triples, 45 SB, 1.003 OPS, 161 OPS+

Unfortunately, the streak came to an end on August 25th, just as it was getting really interesting. Molitor went 0-4 with a strikeout on a cold and rainy night in Milwaukee against Cleveland. Those kinds of games happen in baseball, and are why long hit streaks are so rare. But the way this one ended was especially cruel.

The game was tied at zero after nine and went to extra innings. In the bottom of the tenth, excitement began to ripple through the stands. Molitor was on-deck. It looked like he was going to get an extra chance to keep it going. Then, little-known Rick Manning walked it off with a single.

The Brewers won 1-0 in front of the home crowd and boos poured down on the field. Manning was never really forgiven by the fanbase, but they recovered quickly enough to give Molitor a standing ovation when he returned from the clubhouse to take a curtain call a few minutes later.

In the end, he fell short of DiMaggio’s record by 17 games. Not even close really. But that’s not the point. Playing in baseball’s smallest market, an often unfairly overlooked player captured the spotlight of the entire baseball world and beyond.

Not only that, but he also served as my introduction to Joe DiMaggio. I imagine this is true for a lot of baseball fans my age. I was still very young and fairly new to the game in 1987, and because of Molitor’s streak I realized that the game had existed for a long time before I started watching.

1987 was the first time I heard the song, “Joltin’ Joe DiMaggio.” Not exactly something I’ve kept in constant rotation in my playlist ever since, but let’s face it— it’s far from the worst sports-themed song I’ve ever heard. Looking at you, “Get Metsmerized.”

It was also the first time I ever saw the old black and white clip of the canvas with 56 written across it, followed by DiMaggio cutting it with his bat and stepping through with a grin on his face. I don’t know why, but I thought that was the coolest thing back then. I still think it’s pretty cool.

More importantly, it inspired me to pepper my grandpa with “old-timey” baseball questions. He served as my personal baseball historian back then, and he held DiMaggio in high regard. That meant I did too, which only increased my respect for Molitor by association. This sort of thing would play out again and again over the years, increasing my knowledge of numerous players who had come and gone before I was ever even born.

That’s why the record book really matters. It’s not the records themselves, as impressive as many of them might be. Nor is it the pursuit of them, as thrilling as that can be. No, it’s the connection between the record and the pursuit, which is actually the connection between generations of players and fans.

This is what keeps baseball’s history alive and vital. The book can be tarnished, but it can’t be erased. And you don’t need a pristine record to ignite conversation and arguments, to invite comparisons between eras. You just need a few benchmarks and you’re off and running.

After all, no one thinks any less of Molitor for coming up short of DiMaggio. Both of them are together in Cooperstown now, as they should be, but the thread that ran between them stretched out over four decades, and for one summer, linked baseball fans from at least three generations together.

And that’s way more powerful than any singular stat you’ll find in a book.

Thanks for reading Powder Blue Nostalgia. Do you remember Molitor’s streak? Who was your personal guide to baseball history? Let us know in the comments below. And please share with your seamhead friends and subscribe, if you haven’t already, to get weekly blasts of PBN.