Real quick before we start— I want to encourage everyone to subscribe if you haven’t already. We’re seeing steady growth, but I’d love to see the numbers explode. So please hit that subscribe button and share with everyone you know who might enjoy weekly blasts of classic baseball. It’s totally free, and I promise I’ll never blow up your inbox or do anything shady with your email address. Now, on to the main attraction.

My favorite players tend to be the well-rounded types. By that, I don’t mean that they’re well-read and know how to pick out a good wine for a fancy dinner, though such characteristics obviously wouldn’t hurt their standing either. Okay, I honestly don’t care about the wine thing, but when I heard that Nationals pitcher Sean Doolittle’s favorite activity on the road was to hit up used bookstores, he immediately earned a fan for life.

I’m talking baseball tools here— power, speed, hitting for average, fielding, arm strength, etc. (Pitchers are an entirely different conversation.) Yes, I’ve been open about my admiration for Mark McGwire as kid, but who among us hasn’t been seduced by a slugger at some point? The players I held in the highest regard were the guys who could do a little bit of everything at an All-Star level.

This outlook was likely influenced by the Royals being my hometown team. Long home to some of the league’s paltriest home run records, the championship caliber Royals teams of the 70’s and 80’s were built on speed, defense, and clutch hitting. (And pitching, of course, though again, that is not the focus of this post.)

Their best players, the players who became my heroes, never led the league in home runs. George Brett only hit 30 home runs once in his career. Frank White never did. Willie Wilson’s career high single season HR total was 9. Yet, Wilson hit more inside-the-park home runs than any player since the deadball era and led the AL in triples five times. He also won a batting title in 1982, and George Brett won three of them. Frank White won eight Gold Gloves.

My point is not that there are other plays in baseball just as exciting as a home run, though it is perhaps not a terrible reminder for a sport that sometimes seems like it’s forgotten this fact in recent years. (I’m hopeful that some of the 2023 rule changes will help with this.) Instead, I’m simply emphasizing that to be the best in baseball it takes more than just being really good at one thing. To be the best, a player needs to be the total package.

This is why I eventually realized that Rickey Henderson was a far more important player for the late 80’s Athletics teams I flirted with than McGwire or Jose Canseco. And it explains why the 2014-15 Royals were able to stuff the projections back into the faces of the advanced stats guys and win a title despite being a middling slugging team.

All this isn’t to say that home runs don’t matter. We might put way too much emphasis on them, but there’s a perfectly good reason we love them so much. Dingers are awesome, and they’re just as important as any other category when it comes to determining the best. We just have to weight them correctly.

So this is the criteria I use when I attempt to identify the best baseball player I’ve ever seen. Not surprisingly, two players immediately come to mind. One was probably the most-hyped prospect in the sport’s history, and the other is quite possibly the greatest player of any era, though not without his fair share of controversy. Ironically, it is the former who is in the Hall of Fame, while the latter continues to wait for a call that may never come.

If you haven’t noticed by now, I enjoy picking two players (or teams, or seasons, or whatever) and comparing them head-to-head. And there may be no more fascinating comparison than Ken Griffey Jr. and Barry Bonds. Perhaps it should not be surprising that two of the best players in baseball history have so much in common, but despite these similarities, it is the ways they differ that reveal so much about them both as players and men. They really are mirror images of each other, but sometimes it seems like the mirror came from a funhouse.

Both players were destined for baseball greatness from birth. Their dads didn’t just play pro ball— each of them were great baseball players in their own right. Ken Griffey Sr. was a key part of the Big Red Machine that won two World Series for Cincinnati in the 1970’s, and Bobby Bonds became the first player to join the 30-30 Club in five different seasons for the San Francisco Giants— a feat that has since only been matched by his son. He also joined his Giants teammate (and Barry’s godfather) Willie Mays, as the first two players to ever reach the career 300-300 Club (300 home runs and steals). Barry would also eventually join him in that select group as well, on his way to becoming the only member of the 400-400 and then the 500-500 Clubs.

Bobby Bonds’ career was gradually derailed by nagging injuries and alcoholism, however. Over the course of the second half of his career, in which he was basically a glorified journeyman, the media covered his downfall unmercifully, which undoubtedly influenced Barry’s own antagonistic relationship with the press during his career. That ongoing hostility has done his legacy no favors, and probably cost him the MVP vote to Terry Pendleton in 1991.

It also hurt his draft status coming out of high school. Scouts were turned off by his attitude and lackluster work ethic, and few wanted to deal with his father, who was acting as Barry’s advisor and de facto agent. The Giants took him in the second round, but the two sides couldn’t agree on a deal, so Bonds went to college.

Bonds was an All-American at Arizona State, and led the Sun Devils to the College World Series, but he didn’t win many friends. When he was suspended for missing curfews, ASU coaches wanted to send a message to the “rude, inconsiderate, and self-centered” superstar, and put it up to a team vote to determine whether he should be allowed back on the team. This kind of blew up in their faces when the team voted to tell its best player to hit the road. Unwilling to lose their star, the coaches overruled the team, once again proving that you can get away with anything if you’re talented enough.

After college, Bonds was drafted in the first round (sixth overall) by the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1985. While he came into the league with enough red flags to outfit a May Day parade in the Soviet Union, Ken Griffey Jr., on the other hand, was viewed as the uber prospect when he was drafted number one overall by the Mariners in 1987.

With a golden boy smile, an endearingly simple nickname (“the Kid”), and the sweetest stroke since Ted Williams, he was a baseball reporter’s dream. Seriously, the Kid’s swing was a thing of beauty. If MLB wanted to switch its logo to his silhouette tomorrow, they’d get no argument from me. In his prime, it was nearly as recognizable as Michael Jordan’s Jumpman logo.

Griffey quickly ascended through the minors, and was basically a household name before he ever played a Major League game. Card collectors (including myself) flocked to get their hands on every version of his rookie card that was printed— the Upper Deck card has stood the test of time as the most iconic. Nike and Nintendo and lots of other sponsors lined up to get a piece of him. I’ve already written about my love for Ken Griffey Jr. Presents Major League Baseball for the Super Nintendo.

Most importantly, kids worshipped him. Over the course of my life, currently at forty-three years, I’ve seen very few athletes capture not just an entire generation’s attention, but their love, the way Griffey did. Michael Jordan did it in the NBA. Maybe Lebron James, though like with everything today, he can be polarizing as much as he is beloved. I’m not sure I can come up with a comparable NFL player. I definitely can’t think of another MLB player. We imitated Griffey in the sandlot, at recess in school, and on the fields at little league. From day one, he symbolized greatness on the diamond, and this was only reinforced as his career progressed.

But while things appeared more idyllic in the Griffey camp than with the Bonds family, looks could be deceiving. Griffey Sr. didn’t have the same kind of baggage as the elder Bonds, but the reality was that Bobby and Barry were much closer than the Griffeys.

Depressed and under immense pressure concerning baseball, especially from his father, Junior swallowed 277 aspirin pills in a suicide attempt in January 1988. Fortunately, he survived, but he and his father argued again while he was recovering in the ICU. To make a point, Junior dramatically ripped the IV out of his arm to halt the argument. This did manage to get his dad’s attention, and proved to be a turning point in their relationship. Things did not fix themselves overnight, but they gradually improved their relationship moving forward.

The best evidence of this came in 1990, when Senior signed with the Mariners and the two of them became the first father and son to play together for the same team. On August 31st, they hit back-to-back singles, but the peak moment came two weeks later when they hit back-to-back homers off Angels pitcher Kirk McCaskill. It was a really cool moment. After touching home base, Senior seemed to dare his son to top that when he passed the on-deck circle. When he did, Junior playfully ribbed his dad as he re-entered the dugout.

Griffey was known as a harmless prankster, which was part of his appeal. He appeared to genuinely love the game, and was a positive influence and leader in the clubhouse. Occasionally, outside observers would comment that it looked like he wasn’t giving it his all, but I believe this was another case of looks being deceiving. He wasn’t loafing, but the game came so easily to him that it often looked like he wasn’t going full speed.

And he was so immensely talented that the game really did come easy to him. He doubled off of Dave Stewart, one of the most intimidating pitchers to ever set foot on a mound, in his first career at-bat. A week later, he launched his first home run. 629 more would follow. In 1993, he homered in eight straight games, tying the record set by Don Mattingly (1987) and Dale Long (1956). A thirteen-time All-Star, he won four AL HR titles and three Home Run Derby trophies.

He was far from a one-trick pony at the plate though. His career stats include a lot more than home runs.

And, of course, none of those numbers give you an idea of his defensive wizardry. Griffey won ten Gold Gloves, and I could blather on and on about how great he was with the leather, making diving grabs, stealing home runs by climbing the fence, and gunning down runners on the basepaths, but it would be more effective to just point you in the direction of one of the many highlight reels available on YouTube. You really do have to see it to believe it.

Unfortunately, Griffey’s career reached a turning point following the 1999 season. Despite leading the Mariners to the most successful stretch in franchise history, the culmination of which came in Game 5 of the 1995 ALDS, when Griffey scored from first on Edgar Martinez’s double in the bottom of the eleventh, completing an 0-2 comeback vs. the Yankees, Seattle was beginning to retool.

Griffey was traded to Cincinnati. He requested the trade because he wanted to be closer to family, not because he wanted out of Seattle. In fact, he turned down a deal to go to the Yankees, which would have given him the best chance to win a ring. His first season with the Reds was in line with his previous greatness, but the injuries began in 2001. From 2002-04, he would miss 260 of 486 games.

He was still very good when he was healthy enough to play, and even won the Comeback Player of the Year award in 2005, while continuing to rack up career statistical milestones. But as the injuries added up, the greater toll they took on his play.

In the midst of this, he was honored before a road game in Seattle in 2007, where he was still considered a hero. Mariners fans credited him with being the driving force behind the construction of Safeco Field and insuring that the Mariners stayed in Seattle. He was so touched by the outpouring of love and appreciation from the stands that it paved the way for him to re-sign with the Mariners in 2009 and finish his career in Seattle.

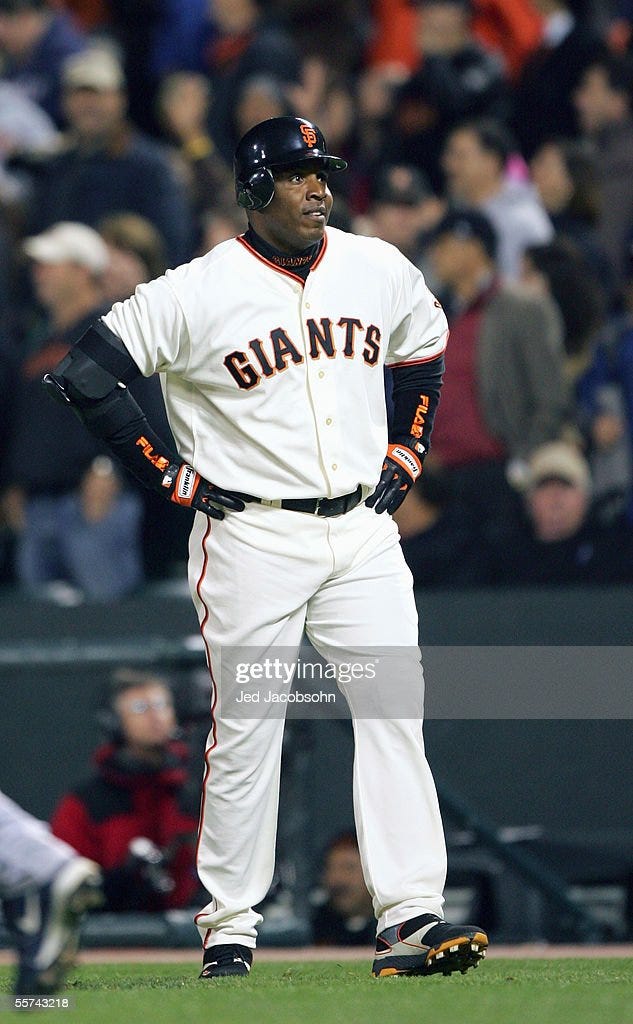

Barry Bonds never received that kind of love in Pittsburgh. He did not arrive in the Steel City with the same kind of fanfare, and initially struggled in CF, forcing the Pirates to trade for Andy Van Slyke and move Bonds to LF. After watching Van Slyke win a Gold Glove, Barry made up his mind to win one of his own. Van Slyke suggested that it had never occurred to Bonds to be a good outfielder, but once he decided to do it, the feat was a forgone conclusion. In 1990, Bonds won the first of eight Gold Gloves.

Bonds, Van Slyke, and Bobby Bonilla formed the core of a Pirates club that won three straight NL East titles, but could never get over the hump and make it to the World Series. He won the NL MVP in 1990 and 1992, and probably should have won it in 1991— no disrespect toward Terry Pendleton. But despite all that success, the fans never really warmed to him and ownership was unable and unwilling to make him the highest paid player in baseball, a raise he felt he deserved. Both the eye test and the stats supported his case, but the Pirates wouldn’t budge, so Bonds went home to San Francisco.

Only in San Francisco would he find a home that embraced him and loved him for who he was. The media would always despise him, a condition he would only make worse by despising them right back, and fans of other teams loathed him. At first, they hated him because he was so good, but that hatred only intensified when PED allegations dogged his career in later years. But no matter what, Giants fans always had his back.

He won his third MVP in 1993, leading the Giants to an impressive 103 wins, but they still finished one game behind the Braves in the NL West. That was the last year before the implementation of the Wild Card game, so there was no postseason at all for the Giants.

In 1996, he joined Jose Canseco (1988) as the second player in the 40-40 Club. Two years later, he became just the fifth player in MLB history to be intentionally walked with the bases loaded in the 9th inning. The Giants were trailing the Diamondback 8-6, and it turned out to be the right call as Arizona held on to win 8-7.

The turning point of Bonds’ career came in 1998 when he watched the fans and media fawn over McGwire and Sammy Sosa as they chased Roger Maris’ single season HR record. Griffey was in the thick of that too for over half the season, until an injury derailed his pursuit. Bonds was without a doubt the superior overall player, but seeing the money and adulation thrown toward the sluggers triggered a jealous streak in Bonds and he began working out with a shady trainer named Greg Anderson.

A lot has been written about Barry Bonds and steroids, and I’m not going to rehash it all here, beyond covering some basic info. Yes, it is true that Bonds never officially tested positive for PEDs, and that even if he had, it wasn’t technically against the rules in the 90’s and early 2000’s. And he has steadfastly denied abusing them. But you’d have to be incredibly naïve to believe he was clean.

Outside of the mountain of circumstantial evidence connecting him to Greg Anderson, Victor Conte, and BALCO (a lab that produced steroids), Bonds’ entire body metamorphosized before Spring Training in 1999. Ironically, Griffey’s head comically ballooned with a case of gigantism in the classic Simpsons episode, “Homer at the Bat,” but it was Bonds’ head that grew in real life. He went from being a world class athlete to a bodybuilder overnight.

We can debate whether steroids help someone hit a baseball, but there’s no argument that they help abusers hit them farther, and Bonds definitely hit a lot of baseballs a long way. In 2001, he broke McGwire’s new HR record by hitting 73 of them. And in 2007, much to the dismay of baseball fans everywhere outside of San Francisco, he broke Hank Aaron’s career HR record of 755, ending up with 762.

His career statline looks like this:

Based on stats alone, it’s no contest. Bonds was better than Griffey. In fact, Bill James once said “Bonds was the best player of the 90’s, and it wasn’t particularly close.” He noted Griffey was always the most popular player, but Bonds was the superior player, and I don’t necessarily disagree with him. But as with the stats, it’s not the whole story.

Note that both players fell just short of the 3,000 hit milestone, albeit for different reasons. Griffey’s later years were affected by injuries, and he was essentially forced into retirement. Had he been healthy throughout the second half of his career, no doubt he would have reached 3,000 hits and many of his other stats would probably be closer in line with Bonds.

Bonds had every intention of playing in 2008, and surely could have, but after the Giants let him go as part of their rebuild, he was so radioactive that no one else would touch him. To this day, he continues to be blacklisted from the Hall of Fame, despite a resume that makes a case for him being the single greatest player of all time.

This is not a decision I personally agree with. I understand it, but considering the proliferation of steroids in baseball in the 90’s and early 2000’s, not to mention the induction of David Ortiz in 2022, despite him being on record with a positive test during his career, it makes no sense to ignore an entire crop of baseball’s biggest stars. Bonds should be in, but steroids should be addressed on both his plaque and any exhibit featuring him.

That’s the real tragedy of the Barry Bonds story. If you took the first half of his career before he ever looked at a PED, he would still be a surefire first ballot Hall of Famer. Yes, I personally liked Griffey better— and Rickey Henderson and George Brett, for that matter— but that unspoiled version of Bonds was better than all of them. Even in that state, he still might have been the greatest player of all time. He might never have broken all those HR records, but he still would have hit plenty, and he was so good at everything else too.

And then he sold out in pursuit of fame and money and adoration, though I’m not sure he ever got the last one. He transformed himself into a generic slugger. Yes, maybe the best slugger there ever was, but that’s all he was, and to get there he sacrificed everything that made him truly great.

That’s why I will always favor Griffey. He is in the Hall of Fame. In fact, he was inducted in 2016, just days after I made my very first visit to Cooperstown. The town was prepping for his induction ceremony, and there was no shortage of Griffey history on display. I doubt a baseball novice like my wife picked up on it, but there was an electricity in the air that week. One of baseball’s true legends was entering its Valhalla, and deservedly so. I’m honored I was able to be part of it, even if only on the most distant fringe. Regardless of whether I believe he belongs or not, I sincerely doubt I would have felt the same way about Bonds.

Obviously, character matters.

Thanks for reading Powder Blue Nostalgia. I think I can guess the answer, but who did you prefer, Bonds or Griffey? Leave your answer or any other feedback in the comments below.

Has Shohei met Griffey Jr levels of love and adoration yet?

Like pretty much every baseball fan from the 90s and onwards, Griffey was one of my favorites. Loved the SNES game, loved the swing, how easy he made playing CF look, the flip down shades at the end of the his ball cap. I really wanted Griffey to be the one who broke Maris’ single season HR record, and I thought he would. But it wasn’t meant to be.