This week’s article has nothing to do with the Minnesota Twins. Nor does it feature the 1988 movie starring Arnold Schwarzenegger and Danny Devito, a film I watched on VHS as a kid more times than I care to admit, but there might be an unlikely parallel in its storyline and what I have in mind here. Stick with me on this one. It’ll come full-circle. Sorta.

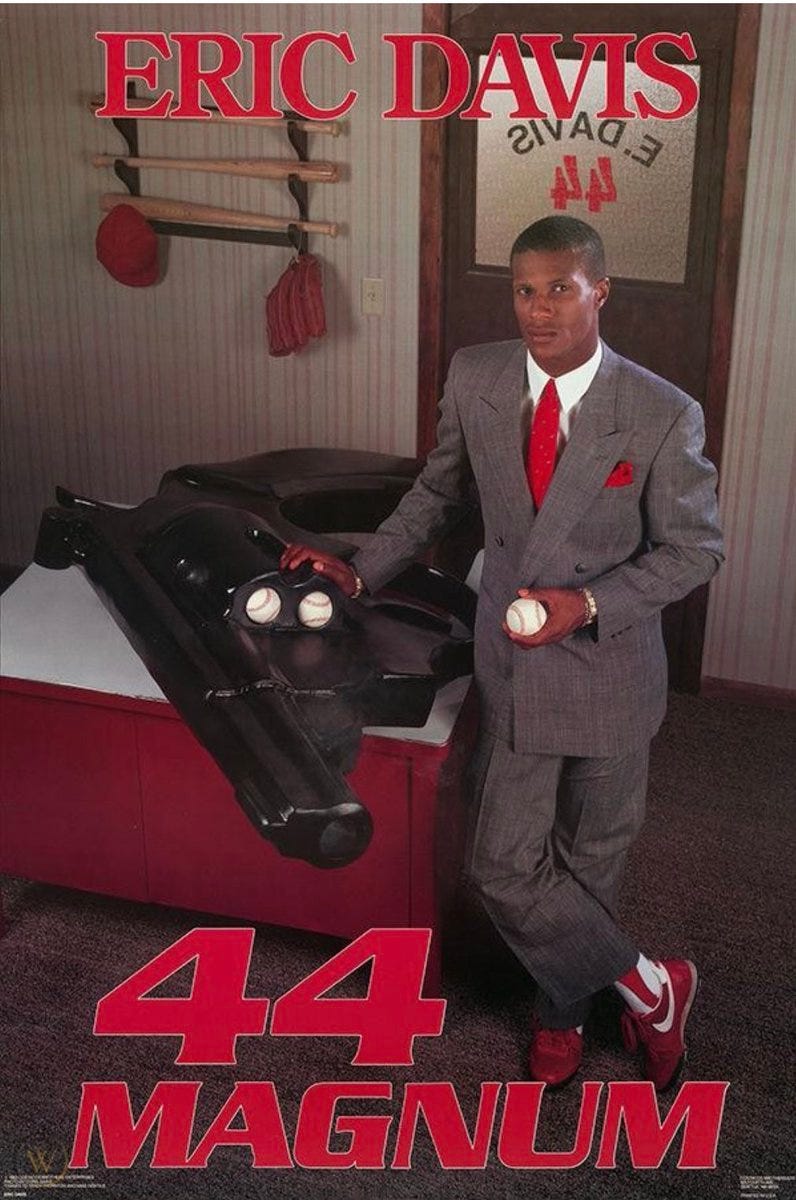

I wanted to write a post about Eric Davis. An outfielder best known for his time with the Cincinnati Reds, he might have a case for being the most underrated player of his era. Not underrated in the sense of Scott Rolen, who I watched for his whole career and considered a perfectly fine player. I never believed Rolen was anything special, however, and I think a lot of baseball fans agreed with me, based on the eye test. Then the sabermetricians began to dig into his stats, and next thing you know, Rolen is being inducted into the Hall of Fame this summer.

Believe me, I’m not trying to dredge up an argument over Rolen or advanced stats. Just stating my own experience watching his career and its aftermath.

I’m not sure I’ve ever heard anyone make a case for Davis being in the HOF. Not a serious one anyway, though I’ve heard lots of Reds fans make the case in the same way I argue for Willie Wilson and Frank White. We know they don’t have a real shot of ever being elected, but we watched them and saw with our own eyes that they were phenomenal baseball players, regardless of whether the stats tell the complete story or not. Those players were so much fun to watch, they helped our teams win games and accomplish feats we could otherwise only dream about, and they earned our undying love and support in the process.

I’ve written about how much Wilson means to me, and I’ll get to Frank White in the future. But I wasn’t a Reds fan, and I didn’t follow them nearly as closely. I knew Eric Davis was good, but I don’t think I ever realized how good he was until I heard Reds fans and other old school seamheads talking him up online, and I started doing research for this article. Hell, I didn’t even know they called him Eric the Red until a few months ago, which only proves how underappreciated he was in his own time, because that is one of the low-key coolest nicknames I’ve ever heard— though I guess that could just be the Medieval history nerd in me.

So the stage was set. I had my subject in place. I was going to shine a spotlight on a criminally underrated player. And then someone nudged him aside and stole the spotlight. This shouldn’t have come as a huge surprise. It’s pretty much par for the course for the consistently underrated, right?

It certainly seems to be the case for Eric Davis. He grew up playing basketball with Byron Scott. Basketball was Davis’s first love, and by all accounts he was really talented at hoops too. He had dreams of playing professionally, but he had no desire to continue his academic career into college, which was the only feasible route for basketball prospects at the time. Instead, he signed a deal with the Reds after they drafted him in the eighth round and jumped straight to professional baseball after high school. He became a star player for the Reds, but even then he was still second fiddle to his future HOFer teammate, Barry Larkin.

So it only makes sense that he would be forced out of the spotlight in his own write-up. Well, maybe not forced out, but forced to share it. I didn’t necessarily want to do it, but when I learned that he grew up in the same neighborhood as Mets legend, Darryl Strawberry, and that they were rivals at crosstown schools as teenagers, I couldn’t help but dig a little further. The two men’s careers and lives mirror each other in so many ways, it soon felt impossible to write about them separately.

The two of them grew up in a rough, gang-infested neighborhood in Los Angeles. Not to go off on too much of a tangent, but I sometimes wonder how my life would have turned out if I’d grown up in that kind of environment. I grew up in a small town that was fairly idyllic (at least on the surface), and actually lived out in the country. Growing up, my closest neighbor was at least half a mile away. This meant I could throw balls up to myself in the yard and scream like Dick Vitale whenever I connected on a deep blast, if Vitale had ever tried his hand at calling baseball, without any fear of embarrassment.

One time, after my exhausted dad returned from a hard day of work in the fields, I insisted he come outside and watch me single-handedly act out an entire game from the 1985 World Series. I was very young, and I have no doubt that it was torture to sit through, but to his credit, my dad did it.

Eric Davis’s father once had to cover his son as they crawled behind the school when someone started shooting toward the basketball court where they were playing. Strawberry’s dad was an alcoholic who used to beat him when he got angry. So believe me, I don’t wish that we could have traded places. But I do occasionally wonder if that relatively safe and stable environment played a role in me (and many of my friends) seeking out trouble when we got a little older. God knows I found plenty of it, effectively derailing my life for years, and it probably gave me more empathy than most for athletes like Strawberry, who encountered his own fair share of adversity later in life.

I’m getting ahead of myself though. As is often the case for young men like Davis and Strawberry, sports provided an escape from their surroundings, and both of them took full advantage of the opportunity.

Of course, whenever the two of them matched up in high school— Davis for John C. Fremont High School and Strawberry for Crenshaw— most of the attention was focused on Strawberry. He was the one the scouts came to see, and journalists made him the centerpiece of their newspaper articles. It was hard not to be captivated by him.

Even at that stage of his young career, people were already calling him the next Ted Williams. That’s an insane amount of pressure and expectation to put on a high school kid, but he appeared to be able to handle it. The game came easy to him, he readily admitted, and when he said it, it didn’t come across as boastful. It was simply a matter-of-fact statement.

Unfortunately, his natural ability was a double-edged sword. Strawberry developed a weak work ethic, simply because he didn’t need to work hard to be good. This resulted in him getting kicked off his high school team at one point, but instead of pouting or throwing a fit like many “superstars” would have done in that position, Strawberry showed a willingness to learn from his mistakes. This was good, because he would make many more over the course of his career and life. He volunteered as a team manager, threw himself into the grunt work, and eventually earned his way back on the team.

The Mets took Strawberry with the number one overall pick in the 1980 Draft. He debuted with the Mets late in the 1983 season, after an up and down tenure in the minors, and hit the ground running in his first full season in 1984, winning the NL Rookie of the Year award.

Davis made his debut with the Reds in 1984 as well. Much more unsung than his Mets counterpart, Reds manager Pete Rose was practically salivating over Davis’s potential. An elite athlete and five-tool player, Rose and the Cincinnati coaching staff were convinced he would be an instant star. The initial returns were disappointing, however. Davis was phenomenal in the field, sacrificing his body and making highlight reel catches on a regular basis, but he struggled with the bat, and was eventually demoted back to AAA.

He could have been disheartened, but like Strawberry in high school, Davis refused to let this bump in the road define him. The demotion worked in his favor, allowing him to work out the kinks in his swing, and it might have even dialed back some of the high expectations placed on him by his own organization. Feeling a little less pressure, Davis returned to the Show and quickly developed into the player Pete Rose envisioned. His true breakout came in 1986, when he joined Barry Bonds as the only player to ever hit 30 HR and steal 50 bases in a season.

Over the course of the next half-decade, Davis and Strawberry cemented themselves as stars and two of the best overall players in the game. From 1986-90, Davis averaged 30 HR and 40 SB a season. Strawberry was just as, if not even more, prolific with the bat over the same amount of time, though not as fleet of foot on the basepaths. That said, he did become the tenth player ever to join the 30-30 Club in 1987.

Their careers were remarkably similar over this span of time, even if Strawberry tended to edge Davis out in certain categories. Davis was a two-time All-Star (1987, 89), and Strawberry was an eight-time All-Star (1984-91), which is probably the biggest disparity on their resumes. But keep in mind that Strawberry was playing in the biggest market in America with the power of the New York fanbase supporting him in the All-Star vote, while Davis was playing in small-market Cincinnati.

Each of them won two Silver Slugger awards, but Davis was a far superior defender, winning three Gold Gloves to Strawberry’s none. Strawberry won an NL Home Run title in 1998, but both of them won a World Series in that time span. Strawberry later won three more with the Yankees during the latter portion of his career— this was well after his prime when he was a part-time player and far from the superstar he was at his peak. I'm not trying to diminish the accomplishment. I’m just pointing out that it’s not easily comparable to what they were doing in their prime.

Strawberry was a superstar on the loaded Mets 1986 championship team, and Davis was a leading force on a Reds team that shocked the baseball world and swept the A’s in the 1990 World Series. Here is how they both fared during their championship seasons.

Davis (1990): .260/.347/.486, 24 HR, 86 RBI, 26 Doubles, 2 Triples, 21 SB, .833 OPS, 123 OPS+

Strawberry (1986): .259/.358/.507, 27 HR, 93 RBI, 27 Doubles, 5 Triples, 28 SB, .865 OPS, 139 OPS+

Not bad, but let’s check out their respective best seasons.

Davis (1987): .293/.399/.593, 37 HR, 100 RBI, 23 Doubles, 4 Triples, 50 SB, .991 OPS, 155 OPS+

Davis finished ninth in the NL MVP voting, and that May he became the only player in MLB history to hit three grand slams in one month. 1989 was probably his second-best season, and the numbers weren’t far off from 1987. For Strawberry, 1988 featured him at the top of his game, though his numbers in 1985 and 1987 were similar. In 1988 though, he led the NL in HR, SLG, and OPS.

Strawberry (1988): .269/.366/.545, 39 HR, 101 RBI, 27 Doubles, 3 Triples, 29 SB, .911 OPS, 165 OPS+

You can make an argument that at their peak, Davis might have even been better than Strawberry, though it’s close, no matter how you look at it. This carries over to their career stats.

Respectable stats across the board, but you wouldn’t be the first one to think they should be even better, especially if you watched the first half-decade of their careers. So what happened? Well, both players ran into obstacles that would significantly sidetrack their careers.

For Davis, it was the injury bug. No one ever accused Davis of being soft, but he played with reckless abandon in the outfield. This resulted in no small number of magnificent catches, but there’s only so much abuse the human body can take.

In fact, his fantastic 1987 season had the potential to be even better, but he only played in 129 games that year, battling several injuries. The worst occurred that September, when he crashed into the brick wall at Wrigley Field. He did make the catch though.

Perhaps his worst injury came during the 1990 World Series. He made a spectacular diving catch in the first inning of Game 4, robbing Willie McGee of a base hit, but lacerated his kidney in the process. He spent the rest of the game and the next forty days in a San Francisco hospital. Upon his release, the Reds initially refused to provide a private plane for the World Series hero to fly home. They eventually relented, but the misstep was enough to get him sideways with the organization.

The relationship between the Mets and their star slugger soured as well. In many ways, the Mets were the worst possible place a young, insecure standout like Strawberry could have ended up. He was a young man who would have benefited immensely from real structure and consequences, but there was none of that to be found in Queens in the 80’s. The Mets were legendary partiers and troublemakers, and in their midst, Strawberry fell prey to his own worst instincts.

Like many of the Mets, Strawberry was using coke and drinking heavily during their run to the championship in 1986. But unlike Dwight Gooden, the young star pitcher, who was quieter and more self-contained and only hurting himself with his coke habit, Strawberry was undisciplined, egotistic, and disruptive.

When manager Davey Johnson pulled him as part of a double-switch late in Game 6 of the World Series, Strawberry called him out to the media and leaned into the controversy. Gooden’s play was already showing adverse effects from his growing addiction, but Strawberry was still producing despite his vices, and he didn’t appreciate being benched with the World Series on the line. As if to prove his point, he led off the bottom of the eighth in Game 7 with a home run that effectively salted away their victory and smoothed everything over.

It couldn’t last forever though. The Mets of the mid-80’s were not built to be sustainable. They were made to burn out fast and fade away, which is what they did. The same appeared to apply to Strawberry. After winning their title in 1986 and reaching the NLCS in 1988, he saw the writing on the wall and left in free agency after the 1990 season.

Strawberry went home to L.A. and became a Dodger. A year later, his relationship with the Reds strained to the breaking point, Davis joined him. The homecoming wasn’t what either of them hoped for. Both spent a few uneventful seasons in Los Angeles and moved on again.

Strawberry’s drug habit was out of control, and facing legal trouble with the IRS, he chose to walk away from the game following the Strike, until George Steinbrenner talked him into joining the Yankees. Steinbrenner had a reputation for being a short-tempered jerk who fired people in a flash, and it was not an undeserved reputation. But while it might be naïve to think he was doing it out of the goodness of his heart— he obviously saw a benefit for his baseball team— I think he should be commended for giving Strawberry a second chance.

Strawberry’s drug problems didn’t go away overnight, and Steinbrenner even assigned a handler to make sure his new acquisition didn’t get too carried away, but Strawberry was able to achieve a kind of career renaissance with the Yankees. True Mets fans still shudder at the sight of him in pinstripes, but Strawberry played a supporting role in three Yankee title runs.

Perhaps his most impressive feat was battling colon cancer in 1999. Coming on the heels of a 140-game drug suspension, he returned from his bout with cancer to hit home runs in both the ALDS and ALCS, helping the Yankees defeat the Rangers and Red Sox on their way to a third World Series title in four years.

In yet another eerie similarity between the two players, Davis was also diagnosed with colon cancer late in his career. He endured a few listless seasons following his Dodgers stint, but after patching things up with the Reds, he returned to Cincinnati in 1996 and won the NL Comeback Player of the Year Award. The Reds didn’t re-sign him, however— Davis blamed manager Ray Knight, a former teammate of Strawberry’s with the Mets, for not supporting his comeback— and he signed with Baltimore.

The 1997 season started off strong, but was derailed when he received his diagnosis. He had a portion of his colon surgically removed in June, but as I’ve made clear, Eric Davis was nothing if not tough. He returned to the Oriole lineup that September, still undergoing chemotherapy, and helped Baltimore clinch the AL East. They went on to beat Seattle in the ALDS, before falling to Cleveland in the ALCS.

Were these the storybook endings fans would have predicted for these two outstanding players in their prime? Perhaps not, but considering all the adversity they endured, even if they brought some of it on themselves, it does feel appropriate. Strawberry found Jesus and appears to have finally gotten clean— hey, whatever works. He raises money to help people fighting cancer and substance abuse. Davis is still active in baseball and works to help disadvantaged kids from rough neighborhoods like the one he and Strawberry grew up in. I can think of a lot worse legacies than that.

So, to circle back to my Twins analogy, which one is Schwarzenegger and which one is DeVito? The answer is neither. Sure, it’s tempting to label Strawberry as the Ah-nold, since he was the bigger star and a coveted athletic specimen from the start. And maybe Davis was the inferior genetic product, since his body eventually broke down on him. Except that wasn’t really the case at all, and if the two of them had been created in a lab, no one would have ever called Eric Davis the leftovers.

Maybe the correct answer is they’re both Schwarzeneggers. Or, if we veer outside the world of the movie and back to real life, maybe they’re both DeVitos. Danny DeVito has never fit the profile of a traditional leading man, but in recent years, the world has seemed to finally recognize his unconventional talent and appeal. The same could be said of Davis and Strawberry.

They were two of the best outfielders of their era, but they never got the adoration of bigger names like Griffey and Bonds. Sure, Davis and Strawberry never achieved the individual glory of those two guys, and maybe they never quite achieved their full potential. Nevertheless, they both put on a hell of a show in their prime, and each of them individually won more championships than Griffey and Bonds combined.

Reds and Mets fans still lovingly reminisce about their exploits, and wouldn’t trade the experience of watching them play for anything. Hell, Reds fans even got the chance to root for Griffey a decade after Davis’s tenure, and it didn’t work out well. A bevy of stars have put on a Mets uniform since Strawberry exited the building, but none of have been quite as electric and entertaining.

That’s because Davis and Strawberry are cult classics.

Thanks for reading Powder Blue Nostalgia. Leave your thoughts on Davis and Strawberry in the comments. Can you think of any other players who mirrored each other like they did?

Fun read, Patrick, and a great POV/theme! From my Astro-perch, and an avid card collector during their careers, I knew all I had to know about them to value their respective cards, and they were certainly fun to watch, and to see if 'Stro pitchers could get them out.

But with all that, I didn't really know about all the drama with each. Sure, I heard about the Strawberry drug issues, and the glass body of Davis. I guess, in the rear-view mirror across decades, it's fun to look back, and you did a great job of Venn diagramming them in prose!

Great stuff! Those two and Bo Jackson...well, if you'd told me and my friends in 1988 that none of them would make Cooperstown, we would have laughed at you. A lot.