Busted

Not every story has a happy ending.

Even though it goes against my natural personality, I try to keep things generally positive when I write about baseball. There’s so much negativity and toxic fandom in the world of sports, and I don’t really feel compelled to add to it. Baseball is supposed to be fun, after all.

Sure, a lifetime of rooting for the Kansas City Royals has often tested that maxim. But I like to think that instead of making me jaded and bitter — don’t get me wrong, it’s definitely done that, but I try not to let it define my overall fan experience — I’ve learned to look for silver linings. More than once, while watching the Royals slog through another 100-loss season, I’ve forced myself to hum the old Monty Python tune, “Always Look on the Brightside of Life.”

But some topics defy a positive spin. This is the case whenever the conversation turns to busts.

I always feel a bit uncomfortable talking about busts. You’re probably thinking to yourself, so why write about it then, dummy? And I don’t have a good answer for you. Busts are just one of those unfortunate realities of sports that no one except trolls take any real pleasure in. But for a newsletter devoted to baseball, it feels disingenuous to ignore the topic altogether.

So let’s be clear about one thing right from the start. Simply making it to The Show is an extraordinary accomplishment. For that matter, even being in a position to be drafted out of high school or college and showing enough potential in the minors to be considered a top prospect is indicative of astounding talent that most of us can only dream of.

I topped out in Little League travel ball myself. My tiny rural high school didn’t have a baseball program in the mid-90’s, or else I probably would have played high school baseball. But it wouldn’t have mattered. Just like playing high school basketball didn’t help me sniff the NBA (and I actually had a pretty decent jump shot), high school baseball wouldn’t have been any kind of stepping stone for me. I might have some fun memories if I’d had the opportunity to play, but I lacked the speed, strength, and overall athletic ability to even become a star player in a 4A Kansas high school league, much less take my career any further.

I’m guessing the same is true of most of my readers, to varying degrees. I have no doubt that many of you were superior ballplayers compared to me. Some of you might have been high school stars, others might have even played college ball or grabbed a cup of coffee in the minors. But unless you made it to the Majors and accomplished something there (of which I believe there are a couple on the subscriber list — total humblebrag), I would caution us all to take a good long look in the mirror before we get too carried tearing down guys who fell just short of dreams the rest of us could only imagine from afar.

Busts happen all the time though. I think back to all the Rated Rookie or Future Star cards I had as a kid, and so many of those names are unrecognizable to me now because they never panned out. And the same is true of top prospects today. Even with all the advances that have been made in scouting and analytics, the vast majority of prospects, from five-tool can’t-miss superstars to workmanlike role players, fail to make it in the big leagues.

This goes to show how tough it is to make an MLB roster and keep your spot. At least, that’s the takeaway we should get from this. But we’re fascinated by busts. I don’t know why. I can’t explain it, but I do believe there is an envious side of human nature that enjoys watching people fail. Or maybe it has something to do with all the stories contained therein. Every bust has their own tale to tell, and while there might be a lot of common ground, no two busts are exactly like.

Even the definition of bust is hard to pin down. The term means something different to everyone, and is usually measured against a wide range of expectations, rather than any concrete criteria. Take Gregg Jefferies, for example.

Jefferies played nearly a decade-and-a-half, and here are his career stats: .289/.344/.421, 126 HR, 663 RBI, 1,593 H, 761 R, 300 doubles, 27 triples, 196 SB, .765 OPS, 107 OPS+, 19.5 WAR. He was also a two-time All-Star.

To an unbiased, objective observer, those numbers are perfectly respectable. Sure, no one is campaigning to put him in the Hall of Fame, but that is a solid career and he should feel no shame whatsoever. But that’s where things get tricky.

We don’t live in a bubble, and many people consider Jefferies a bust because he wasn’t supposed to be a solid player. Listening to the pundits before his debut, you would have thought he was the second coming of Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle all rolled into one. Were those expectations fair? Of course not, but that’s what he was saddled with, and that’s the prism through which he’ll always be viewed.

As a rookie in 1987, he was supposed to lead the defending champion Mets into the second stage of a dynastic run. Never mind that the Mets were never built for long-term success. Their clubhouse was super-talented, but way too combustible to last. None of that was Jefferies’ fault, but when he posted middling numbers and the Mets fell back to the pack, guess who got a lot of the blame? It should be pointed out that Jefferies did not always publicly comport himself in the best manner to help his case, but it probably wouldn’t have made much difference in the long run.

After the 1991 season, he was shipped to Kansas City as part of a three-player package for Bret Saberhagen. I’ve written about how this was one of the most heartbreaking days in my life as a Royals fan, but Jefferies was the one sliver of hope I clung to in the immediate aftermath. If he finally lived up to his potential, I thought, the deal might not be a complete disaster. He might even add his name to the list of Royals greats, if all went well. He didn’t have to be the next George Brett, but it wasn’t outside the realm of possibility that a guy with his pedigree could join the ranks of Amos Otis, Willie Wilson, and Frank White. Unfortunately, he never really put it together until he moved onto St. Louis the following year.

Jefferies’ time in St. Louis was the most productive of his career, and he made the All-Star game in both of his seasons playing under the shadow of the Arch, and parlayed his success into a big money deal with the Phillies in 1995. He was okay in Philadelphia, but gradually became a journeyman-like player over the last few years of his career. I hesitated to include him at all in this article, but right or wrong, that’s the perception. To me, however, a bust is a player with massive expectations who lays an egg in the big time.

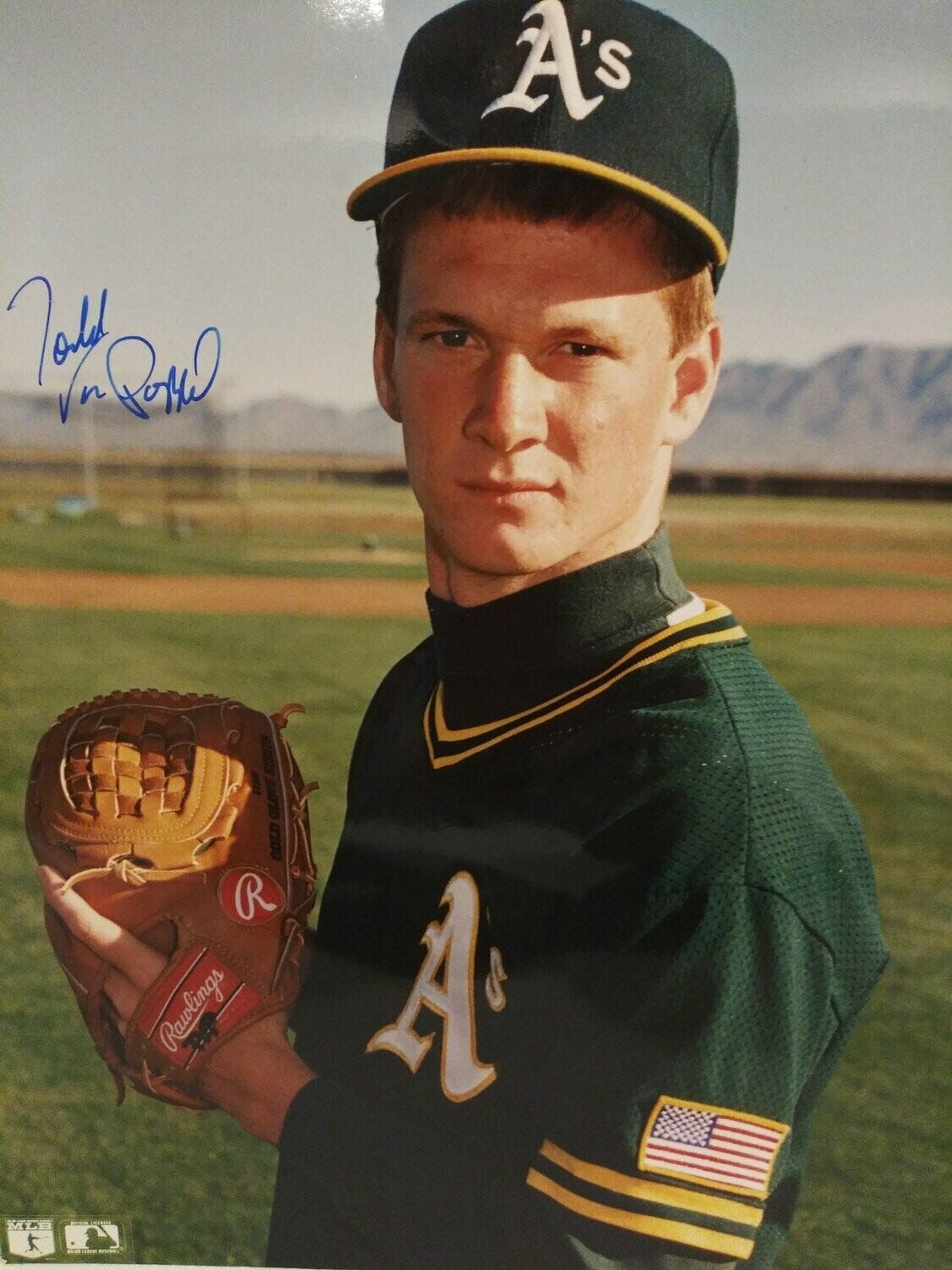

In my lifetime, there is no better example of a bust than Todd Van Poppel. I don’t know anything about him personally. He may be a sweetheart of a guy, though I kind of hope he’s a jerk. Then I wouldn’t feel as bad for all the things I’m going to say about him. But there’s nothing complimentary I can say about his professional baseball career, and just this once, I’m going to ignore my mom’s advice to keep my mouth shut if I can’t think of anything nice to say. Let’s dive into Todd Van Poppel.

Van Poppel was the 14th overall pick in the first round of the 1990 draft by the Oakland Athletics. Back then, coverage of the MLB draft and the minor leagues was sparse. Only true hardcore baseball nerds knew much about prospects, and I don’t know where they were getting their information from. Other than a handful of magazines, there were no websites or social media devoted to covering the lower rungs of baseball. Van Poppel was the exception though. Somehow, he broke through to baseball’s mainstream straight out of high school.

It didn’t hurt that the A’s were at the top of their game in 1990, on their way to a third straight World Series appearance. Buoyed by Dave Stewart and Bob Welch, Van Poppel was supposed to be the next ace of the staff. And he wasn’t coming alone. The A’s took four pitchers in the first 36 picks of the 1990 draft (Van Poppel being the first), similar to the Royals’ pitcher-heavy 2018 draft. And if you’re familiar with how that’s worked out so far, I’ll point out that the A’s luck was just as bad. Probably worse actually, because despite his inconsistencies, none of the A’s picks ever matched what Brady Singer has already accomplished, including Van Poppel.

That wasn’t how it was supposed to go. Van Poppel looked like the obvious choice for the number one overall pick, a can’t-miss pitching version of Ken Griffey Jr., but he warned the Braves that he wouldn’t sign with them if they drafted him. In hindsight, this should have been a massive red flag.

The Braves were traditional doormats, but they were on the rise. In 1991, they turned it around and reached the first of five World Series in fifteen years. They had arguably the best starting pitching rotation in baseball history (which I wrote about last week), all of whose careers would have synced up nicely with Van Poppel’s timeline. Compare that to the A’s, an aging team about to take a downward swing. Can you imagine what Van Poppel might have been if he’d been brought along slowly by the Braves and joined a rotation filled with Maddux, Glavine, Smoltz, and Avery? But that wasn’t how it played out, and Braves drafted some third baseman named Chipper Jones instead. Talk about dodging a bullet.

Van Poppel, on the other hand, was rushed through the minors, despite dealing with multiple injuries. The A’s pitching staff was getting old fast and they needed reinforcements, but Van Poppel was shellacked from the moment he took a big league mound. His fastball had plenty of velocity, but no movement at all, and Major League hitters feasted on it. Injuries and a lack of success meant he didn’t pitch in Oakland again until 1993, and the results weren’t much better the second time around. His best season was probably 1995, but look at his stats and you’ll see that best is a relative term.

1995 stats: 4-8, 4.88 ERA, 122 K, 56 BB, 138.1 IP (Worked as both a starter and reliever.)

Career stats: 40-52, 5.68 ERA, 359 G, 98 GS, 4 saves, 907 IP, 711 K, 1.549 WHIP, 0.3 WAR

So yeah, no one is going to be confusing him with Bob Gibson anytime soon. He was released midway through the 1996 season, less than half a season removed from his “career year,” and bounced around to six different teams. (So, at the very least, he could be a useful piece for you Immaculate Grid players.) Amazingly, he played until 2004.

That’s probably the best compliment I can give him. The most hyped pitching prospect of my childhood never gave up, even if he probably should have. Because, like it or not, there’s no other way to describe him other than a bust.

As always, thanks for reading Powder Blue Nostalgia. I hope you’re enjoying the holidays, and I know it goes against the spirit of the season, but let me hear your picks for biggest MLB busts in the comments. Or share your thoughts on Todd Van Poppel and Gregg Jefferies.

Good topic! I think of Jefferies in the same light as a Trot Nixon, who ended up having a gritty, serviceable career, but was never the superstar that he had been projected to be. And of course, from Boston we had Phil Plantier, who crushed 33 homers while in Pawtucket, but then could never quite make that translate at Fenway. And there was Craig Hansen, straight out of St. John's and brought to Boston too quickly. Instead of being the dominant closer of the future, Hansen found himself quickly out of Major League Baseball.

VP was David Clyde lite. Who remembers him?